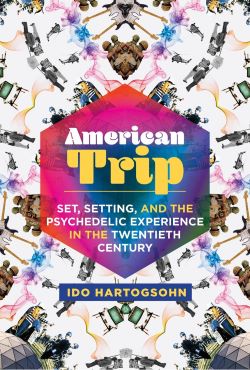

The Psychedelic Dictionary: Psychedelia and Entheogenia

The article was originally published on the Psychedelic Press website.

“Psychedelics” and “Entheogens” are two names for the same group of psychoactive compounds (usually referred to as “psychedelics”). These two terms delineate two very different perspectives on the proper way to use these psychoactive compounds.

“Psychedelic” is a term which was invented by the British psychiatrist Humphry Osmond in 1957, during a correspondence with Aldous Huxley, as the two were trying to find a new designation for the psychopharmacological group of substances which included compounds such as mescaline, LSD, and the psilocybin (found in magic mushrooms). The new name was supposed to replace terms such as “psychotomimetics” (psychosis-mimicking drugs) or “hallucinogens”, two term which were deemed biased and misleading since they falsely present the type of experiences to be had with psychedelics as pathological or conversely as imaginary and without relation to reality. The etymology of the word “psychedelic” is in the two Greek words: “psyche” (mind) and “delos” (manifesting).

“Entheogenic” is a term whose meaning in Greek is “generating the divine within”. It is used to refer to the same group of substances as “psychedelic”. This term was coined in 1979 by a group of researchers which included prominent figures of psychedelic scholarship such as classicist Carl Ruck, ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes and mycologist R. Gordon Wasson. The neologism was introduced due to a general feeling that the term “psychedelic” has become too strongly identified with the excessive drug culture of the 1960s and damages the unbiased discourse about traditional or religious use of “psychedelics” within a shamanic or spiritual context.

Ever since the invention of the term “entheognic”, the two words have come to designate two different approaches in regards to the proper ways to experiment with the same group of plants and molecules. While the first one relates to mostly free-style experimentation, the other relates to experiences in which religious intention plays a fundamental role.[1]

Psychedelia and entheogenia are complementary in many ways. Both are ways to increase our understanding of the universe and of ourselves; To live more fully, to love and to appreciate. And yet, they are both are fundamentally different paths, defined by fundamentally different attitudes and style. For example, many of those who support entheogenic work (i.e. shamanic or ceremonial use of power plants), discourage the “psychedelic” use of such substances as irresponsible and lacking respect. At the same time, many of those who champion the psychedelic approach regard the entheogenic approach to be too ceremonial, maybe even dogmatic, or just prefer to experiment freely without any ceremonial restraints.

In this essay I would like to examine the roots of these two approaches and assert that despite the major differences, these two approaches can actually complement each other, enrich each other, and give birth to a balanced fertile path for the use of psychedelics.

The psychedelic element

The psychedelic element is chaotic. Psychedelic use nourishes itself on colorful and often surprising interactions between the drug experience and the external world. These are the qualities which make it so interesting. The psychedelic path is epitomized in the figures of Ken Kesey, Stephen Gaskin and Hunter S. Thompson who turned the hallucinating exploration of reality into a form of art. In its root lies a basic call for psychonautic adventure, for a breathless and sometimes even frightening journey into the visionary worlds of consciousness and the symbolic bowels of the world around.

The psychedelic element has a strong relation to liminal states of consciousness, and in this respect those who called the psychedelics “psychotomimetics” or “psychosis-mimicking drugs” were right. This was conceded even by the greatest opponents of the psychotomimetic hypothesis such as Huxley and Leary.[2] However, in contrast to those psychotomimetic scientists who viewed these substances as psychosis mimicking and little else, for Huxley, Osmond, Leary and the other psychedelic researchers, the psychosis-like phenomena which were sometimes part of the psychedelic experience, were of essential meaning, but one to be overcome and transcended. The phenomena also held an important lesson about the nature of madness. As Allan Watts writes in his essay about the psychedelic experience, “The Joyous Cosmology”: “No one is more dangerously insane than one who is sane all the time: he is like a steel bridge without flexibility, and the order of his life is rigid and brittle”. Only the person who understands the meaning of madness, who knows what it means to be insane, can be truly sane. Only the person who understands the depths of insanity can choose sanity in its deepest sense, whereas the sanity of the person who refuses to gaze at insanity is nothing more than a thin and brittle shell under which lies a deep abyss.

The Entheogenic Element

The entheogenic element is centered. In contrast to psychedelic experimentation the entheogenic work is ceremonial and focused around prayer, meditation or healing processes. It takes place in a sheltered environment and often with the guidance or company of other experienced voyagers or healers. Thus, entheogenic work tends to be safer than the sometimes chaotic psychedelic experimentation.[3]

Entheogenia is a boot camp for psychedelia. It Is the school in which one learns the discipline. It gives one tools and techniques for work with psychedelics. It strengthens one, teaches proper ways to work with psychedelics, and deepens one’s knowledge of them. It turns them into allies in the sense meant by Castaneda: it gives a person a safe and sacred environment in which he is able to get to know these substances, to know himself, to become firmer and develop knowledge – a knowledge which enables one to be stronger later when he is in the midst of the psychedelic battle, because he has developed firmness, knowledge and power.

Chaos vs. Order

Psychedelia is characterized by a greater amount of freedom in comparison to entheogenia. Psychedelia allows one to experiment with a wider scope of activities, than the entheogenic ceremony which has a singular and permanent center: to be able to converse with friends, walk around in nature, write, read, draw, watch a movie and perhaps also to put yourself in more extreme surroundings such as colorful parties, the streets of the city, or say a circus.

While entheogenia is a focused, takes place in a controlled environment and is characterized by a well-known and regular order (a shamanic ceremony, or a book of hymns such as those used by many contemporary ayahuasca groups and religions) and seeks to avoid unforeseen distractions, psychedelic use is characterized by its openness to unforeseeable elements, sometimes even it chaoticness. The psychedelic path is one in which the magical state of consciousness unleashed by psychedelics is interfaced with the external (and internal) worlds. Psychedelics act as consciousness fermenting agents, as a kind of magnifying/diminishing/distorting glass which transforms colors, sounds, thoughts, ideas, smells, emotions and what not, and which is used to gain a new perspective on the external and internal world to create an immense variety of experiences.

Psychedelia is the DJ who uses up everyday elements and mixes them into exciting new cosmic combinations. It confronts the unknown and synthesizes novel structures of experience with unforeseeable results: eating mushrooms in a park with your friends and achieving new levels of interpersonal intimacy; Going to the cinema after eating a trip to watch a 3D film and enter a parallel world; Visiting the town where you grew up after many years escorted by a molecule which makes you reevaluate your childhood, your roots and who you are. Then maybe even go to the shopping mall under the influence and get shocked but also understand consumer culture on a whole new level.

The psychedelic state is a state of stimulation. We need stimulation, especially when we are immersed in monotonous everyday existence which leads to apathy. The psychedelic wake-up call frees one for the everyday banality of the domesticated consumer-citizen of late capitalism, thus supplying a basis for deep exploration of inner and outer identity, of world and cosmos. However, the stimulation inherent in the psychedelic experience is also its more dangerous aspect: Excessively rapid and violent jolts might unstitch the frail seams of the psyche. Too intensive psychedelic work with not enough intention, rootedness and processing time can lead to the eruption of a crisis.

Entheogenia functions as a balancing and anchoring element for psychedelia. Both are in a sense a kind of yin and yang: opposing forces or paths which complement each other and give those who stride their course a full way of life in balancing the cosmic elements of chaos and order.

Transcendence vs. Immanence

While entheogenia is focused on creating a a connection with the god-light of oneness, to a transcendental experience,[4] psychedelia is aimed at connecting with the divine within the world, with immanence.

The entheogenic experience is a ceremonial experience which turns its gaze towards infinity/the white light/ensof. It’s highest goal (Even though it is not always achieved or even sought after) is the dissolution of the ego and it’s boundaries and unification with the God/Spirit/the divine through mediation or prayer (Uniomytica). Entheogens act as an accessory to prayer, meditation and healing which allows one to pray or meditate more deeply, powerfully and meaningfully – opening the path to unification with God in a way which is otherwise unavailable to those who are not part of the rare few born with the natural proclivities of mystics, as described by William James in his Varieties of Religious Experience.[5]

The psychedelic experience, in comparison, is more focused in the experience of the world in which we live. It is a re-living, a boosted, enriched re-experience of the things which you already know in the world, and which now gain new meaning and magic. Understanding your relations with a closer person in a new way, understanding art in a new way, relating to nature in a new way, relating to your body in a new way, relating to yourself in a new way. Psychedelia allows one to see every aspect of reality with fresh eyes. It allows one to inject deeper knowledge and imagination into the everyday life in ways which can foster growth.

While the entheogenic experience is often focused in the relation with the unity of things, the psychedelic experience is often related to the experience of the many. Whereas the entheogenic experience is basically a spiritual experience, the psychedelic experience is to a great extent a cultural experience.[6]

The Golden Path

Some people will always prefer psychedelic experiences over entheogenic rituals, while others will feel the opposite way. These differences are to a great extent the result of differences in temperament and style. Psychedelic people are often wilder, more anarchic in nature, less discriminating about using chemicals and non-psychedelic drugs and will demand a more spontaneous, flexible relation to the drug experience. Entheogenic people, in contrast often tend to have a more rooted style of life, with a more structured and regular form of spirituality, and are guided by firm principles about the proper way to use entheogens (which they will never call drugs, but “medicines”). In a way, one could say that psychedelia represents the secular, cultural aspects of the drug experience while entheogenia represents the spiritual aspects.

From my personal perspective it is recommendable for any psychedelic person to explore the entheognic world at some stage in his life (given the opportunity to do entheogenic work with honest experienced people). The entheogenic element is to my mind crucial in preventing the banalization of the psychedelic experience, which might become repetitive and aimless without the clear line supplied by entheogenia. The entheogenic element functions as a balancing force which guards one from the too violent jolts and shakes which sometimes occur due to intensive psychedelic use.

It is hard for me to say whether it is recommendable for every entheogenic person to explore the psychedelic path. While a psychedelic person would normally have no basic principals which prohibit from participating in an entheogenic experience, the religious character of entheogenia sometimes prohibits “recreational use” of psychedelics. The use of power plants for non explicitly religious purposes might seem as sacrilege. Maria Sabina, the legendary shaman who led Gordon Wasson on his first mushroom experience in the Mexican Oaxaca mountains in Mexico in 1955 claimed that after the westerns flocked the area in search of the mushrooms, the mushrooms had lost their power. This can be a valid reason to make a distinction and avoid using a plant with whom we work ritually for recreational purposes. The entheogenic approach to the sacred power plants is imbued with so much delicacy, love and awe that it is worthy of protecting. Truly sacred values, ideas and objects are so rare in this chaotic postmodern world in which we live, that preserving them demands a devout relationship of love and respect, so that they remain this way. For this reason for example many of those who drink Ayahuasca in ceremonial setting would never drink it at home, even though they might do that with mushrooms.[7] However, in my opinion the importance of spiritual work does not categorically negate the validity and importance of the wild psychedelic experience in the style of Kesey, Gaskin and Hunter S. Thompson. That kind of idea, although it might be more politically acceptable, actually ushers in a kind of psychopharmacological Puritanism which many of the proponents of the psychedelic experience such as Leary and McKenna warned us against.[8] And anyway, it is clear than many people have a deep-felt need for both aspects.

***

The idea that the psychedelic and entheogenic paths can and should exist side by side is not new. It has been around ever since that historical moment when Allen Ginsberg, the first seer of the psychedelic revolution of the sixties had his first mushroom trip in December 1960. I will close the essay by citing from Timothy Leary’s first (of many) autobiography “High Priest” which describes the original psychedelic vision which Ginsberg had on that day. In a reality where the two schools of psychedelia and entheogenia often seem disconnected or at odds with each other, it is worth going back to the innocence and lucidity of the original vision received by Ginberg:

“And then we started planning the psychedelic revolution. Allen wanted everyone to have the mushrooms. Who has the right to keep them from someone else? And there should be freedom for all sorts of rituals, too. The doctors could have them and there should be Curanderos, and all sorts of good new holy rituals that could be developed and ministers have to be involved. Although the church is naturally and automatically opposed to mushroom visions, still the experience is basically religious and some ministers would see it and start using them. But with all these groups and organizations and new rituals there still had to be room for the single, lone, unattached, non-groupy individual to take the mushrooms and go off and follow this own rituals – brood big cosmic thoughts by the sea or roam through the streets of New York, high and restless, thinking poetry, and writers and poets and artists to work out whatever they were working out.” (Timothy Leary. High Priest. P. 25).

[1] It is important to note that the distinction presented here between these two terms is not as clear cut in the discourse of today’s psychedelic community, and many might use these two terms interchangeably. Also, the word “psychedelic” was used for both meanings in the psychedelic discourse of the sixties, before the invention of the term “entheogenic”. The distinction between “psychedelic” and “entheogenic” presented here is a meant to highlight a basic principle in the discourse of psychonautics, based on the common use of these terms in contemporary psychededelic/entheogenic discourse.

[2] See for example Leary, Metzner & Alpert. The Psychedelic Experience. p. 24.

[3] The number of psychedelic casualties is significantly smaller (up to almost non-existent) in native societies which use these plants traditionally as well as in contemporary ayahuasca religions when compared with recreational psychedelic users.

[4] Even though it has pronounced immanent aspects, in as much as man finds the divine within.

[5] Some mystics can of course achieve entheogenic levels of awareness without entheogenic means. Also, peak experiences which resemble psychedelic peak experiences might happen at certain points in a person’s life such as when falling in love, in the birth of a first child or after 40 hours without sleep. Such experiences however happen very rarely and unexpectedly for most people, and as the late McKenna used to say, psychedelics are the only way we know that allows us to access these states of consciousness quickly, reliably and in a way which can be empirically recreated, with the smallest risk in comparison to other techniques used throughout history.

[6] That is. It can also be cultural, but it will most often also include cultural elements.

[7] Of course respecting and protecting the sacredness of your power plant is a delicate matter even when one partakes solely in entheogenic work.

[8] See for example Paul Krassner’s interview with Leary, published in Leary’s “Politics of Experience”, where Krassner charges Leary that his campaign for the religious use to psychedelia has neglected the rights of all those who simply want “to get high”. Leary defends himself there, proclaiming the right to get high without any particular agenda or ideology to be a basic human right.

Great post! I wrote a related article about how we should resist dogma and be open to new entheogenic traditions, embracing the diversity of human experiences and approaches. “Sacredness is in the eye of the beholder” — http://www.psychedelicfrontier.com/2013/04/17/sacredness-is-in-the-eye-of-the-beholder/

I would whine about your oversimplification of the two terms, but I understand that you’re using them to frame a valuable comparison between two different approaches.

I think it’s very rare to have an experience that is purely psychedelic or entheogenic as you have defined them — most experiences with these chemicals are likely to have aspects of both approaches. On one hand the experience is too broad and expansive to be contained by any particular tradition, no matter how sacred, so a bit of free-wheeling exploratory psychedelia will naturally creep in. On the other hand, I think there are plenty of recreational users with purely leisurely intentions who end up having intense religious or at self-analytical experiences that could be described as healing and entheogenic — even if by accident!

I guess I come down on the psychedelic side because I find any single tradition to be too limiting. That said, entheogenic aspects such as deep respect for the experience and thoughtful post-trip integration have become very important to me. I just choose to refine my own sacred ritual rather than subscribing to an existing one.