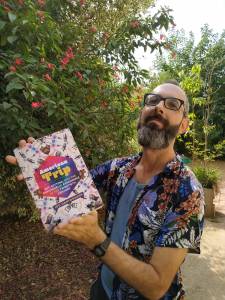

My book American Trip: Set, Setting and the Psychedelic Experience in the 20th Century is appearing today with MIT Press and I’m incredibly proud and excited!

I’ve started working on this book over a decade ago, and it became the center of an intellectual and personal odyssey that led, among other things, to a series of groundbreaking papers that expanded our understanding of psychedelic experiences and their relation to context (set and setting)

I’ve started working on this book over a decade ago, and it became the center of an intellectual and personal odyssey that led, among other things, to a series of groundbreaking papers that expanded our understanding of psychedelic experiences and their relation to context (set and setting)

The concept of set and setting is undoubtedly the single-most central concept of modern psychedelic discourse. It points to the fact that the psychedelic experience has multiple potential modi. There is no ONE psychedelic experience, but rather that experience changes and transforms in relation to context.

The new book takes this idea to its final conclusion. It not only carefully describes how set and setting shapes experiences with psychedelics, but it also engages the broader more interesting questions like: how has the set and setting of contemporary Western culture shaped the psychedelic experience as we know it? How are our ideas of psychedelics and their effects shaped by our sociocultural settings?

The discourse on set and setting is commonly focused on the micro: Who is having the experience? Where? With whom? Carrying which intentions and expectations? Integrating how? These are all important questions, but the analysis was missing a key aspect: the fact that the set and the setting of a psychedelic experience are always rooted in a broader historical and cultural set and setting. All elements of individual set and setting are dependent on historical and sociocultural contexts. From expectations and intentions, to space, people and cultural beliefs.

American Trip is the first book to put the concept of set and setting in this wider context. It departs from the premise that the set and setting of a psychedelic experience never exists in a vacuum but always as a part of a broader historical and sociocultural context.

American Trip is the first book to put the concept of set and setting in this wider context. It departs from the premise that the set and setting of a psychedelic experience never exists in a vacuum but always as a part of a broader historical and sociocultural context.

I’ve started writing of this book with an intriguing question on my mind: if we accept the common cliché that says that the sixties were like one long collective trip, what can the idea of set and setting teach us about the progression of this trip? i.e. what was the set and setting for this collective trip? How did the historical and cultural contexts of the 1960s shape this trip? And how have historical and cultural developments shaped the way we understand and experience psychedelics today?

The writing of this book led me to seven distinct schools of psychedelic research and use, from the psychotherapeutic to the military and from the spiritual to the artistic and the entrepreneurial. Each of these schools created its own micro-climate of set and setting, reshaping the psychedelic experience, producing wildly-divergent types of results, and – consequently – also immensely confusing researchers at the time.

The writing process also led me to explore a host of events and movements that shaped and sometimes continue to shape our perceptions of psychedelia: from the cold war to the sexual revolution, from cybernetics to the anti-psychiatry movement. Along the way I’ve learned to understand LSD as a psychedelic technology, literally a mind-manifesting technology – a technology that changes its colors, features and functions in relation to the various contexts in which it is injected.

I want to thank everybody who helped this book arrive to the world. My hope is that American Trip will provide us with new tools with which to think about psychedelics, and allow us to arrive at a richer, fuller understanding of psychedelic experiences in their social, historical and cultural contexts.

I know it’s not my place to say, but the new book is not only innovative and profound but also highly readable and entertaining, so I encourage you to get your own copy NOW (!) (here’s a link to BookDepository which seem to have better deals on the book) and let me know what you thought about it.

Here, finally, is the readers’ praise for American Trip.

American Trip presents a timely and invaluable guide to the crucial lessons that twentieth-century psychedelic history provides for the current psychedelic renaissance, and to using set and setting as a strategic tool for ensuring the healthy integration of psychedelics into society.

RICK DOBLIN, Founder and Executive Director of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).

In clearly and rigorously exploring the single most consequential idea in psychedelic studies—the notion of set and setting—American Trip not only insightfully reframes the many histories of LSD, but offers a humanistic and reflexive alternative to the often simplistic discourse of today’s growing psychedelic industry.

ERIK DAVIS, author of High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies.

American Trip guides its readers through the reflexive arts and sciences of set and setting used to study psychedelics, beckoning towards an intense pluriverse, full of beguiling guises, strange twists, and thrice-told tales.

NANCY D. CAMPBELL, Professor of Science and Technology Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, author of OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose

In this landmark book, Hartogsohn enlarges the traditional parameters of set and setting by including the larger social-cultural matrix. This expanded definition provides a more sophisticated understanding on how non-drug factors determine the nature of any psychedelic drug experience.

RICK STRASSMAN MD, Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry, University of New Mexico School of Medicine Author, DMT: The Spirit Molecule

American Trip amounts to a sociological enlightenment of our drug culture. Hartogsohn’s vibrant book shows how 1960s America made psychedelics do what they did and suggests that these wondrous molecules will do something altogether different in other times and places.

NICOLAS LANGLITZ, Associate Professor of Anthropology at the New School for Social Research, author of Neuropsychedelia: The Revival of Hallucinogen Research since the Decade of the Brain

Problems are also opportunities to try something new and exciting. Sometimes, that something is an internet website. In April 2010 I had a recurring problem. Over the years I have developed a deep penchant for colorful, multidimensional psychedelic videos that paint pink arabesques in your mind. The only problem was that the types of unique, alternative mindstates in which such videos are superbly enjoyable are the same type of states where navigating the menus and folders on your desktop proves particularly daunting. God gives psychedelic nuts to those who have not teeth.

As a solution, I decided to start a blog that will serve as a reservoir for these psychedelic videos so that they are easily accessible to scroll through every time I need them. Since the problem appeared to be universal, I decided to make the blog public so that every person who is in dire need of psychedelic videos to feed their soul on, would be able to access them easily. And to make things more interesting I added a concept. The website will have specific rhythm: one psychedelic video a day. And so, the Daily Psychedelic Video (DPV) got started, the first website dedicated to psychedelic videos.

A month passed, and I realized that posting one psychedelic video every day is beyond my abilities. Consequently, the DPV got its international team of seven editors for seven days of the week. This had an immediate advantage. The concept of “psychedelic video” is somewhat vague and means different things to different people. When I started the website, I was surprised by the types of videos people sent me. Some of this stuff was really different from my own definition of a psychedelic video. When the other editors joined in, I understood they were essential to the project. Each had a different vision of psychedelic videos. Since then, we generally keep an open mind and one main guideline: a psychedelic video is every video that’s particularly enjoyable and amazing to watch in a psychedelic mindstate.

When we started the DPV in 2010 people told me we would run out of videos in a couple of months. There aren’t that many psychedelic videos out there! People I talked to could each recommend 2-3 videos worth having on the website, but it was not clear how many other psychedelic videos were out there. Actually, as we kept going, we discovered psychedelic videos are getting created faster than we can post them. The second decade of the 21st century saw a boom in the psychedelic video style. The rapid growth of websites like YouTube and Vimeo, the growing availability of digital production tools and the thriving of online artist communities led to a situation where more psychedelic videos were being made each month than had been made during a whole year or even a whole decade in the past. The widely publicized renaissance in psychedelic research was also accompanied by a renaissance in psychedelic creativity. Even pop stars like Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Azealia Banks, Miley Cyrus and Nikki Minaj started churning their own psychedelic videos.

The years passed, and what started as a personal collection kept growing. Every year’s end, I spent dozens of hours watching hundreds of psychedelic videos to curate the year’s best-of list, and these growing lists led to public screenings and even a philosophical paper exploring the aesthetic principles and therapeutic qualities of psychedelic videos (available at the new museum). The website has long become the world’s largest collection of psychedelic videos. There was only one problem. When you got to the website what you got was today’s post, and then yesterday’s post. There was no way to navigate all the intricate richness of psychedelic beauty that was amassed over a decade of exploring psychedelic media.

Again, a problem, and again the solution was found in a new website. The new idea was to take all of the knowledge that was aggregated over a decade of collecting and curating psychedelic videos to create a website of a different type: a museum that includes carefully curated exhibitions of the best, most beautiful psychedelic video works ever created. Since the museum is virtual, we didn’t need the large sums of money you need to erect a museum in physical space. And since all this abundance was already made widely available through YouTube and Vimeo (we’re just collecting and embedding) we also didn’t need any money to buy the art.

The new museum includes 45 exhibitions arranged by theme, style, period and place. You can find exhibitions like “Soviet Psychedelia,” “Japanese Psychedelia,” “1970s Psychedelia,” “Psychedelic Art,” “Psychedelic Cinema,” “Psychedelic Animation,” “Psychedelic Hip Hop,” “Tribal Psychedelia,” and “Psychedelic Activism.” Each of the exhibitions showcases a different aspect of psychedelic creativity.

We’ve built the museum planning to launch it on the 19th of April, on Bicycle Day, which is also the tenth anniversary for the DPV. Then corona happened and we started wondering whether now is the right time to launch. But as the pandemic spread, we realized that now, with people staying home, there is special value in this collection of beauty and creativity. Since the corona pandemic began many people have been talking about the need for virtual museums but many of the existing virtual museums are just pale versions of their physical selves. Digital JPG’s of 19th century oil paintings. The Psychedelic Video Museum is native to the net. It was designed to be virtual, and you don’t lose anything by visiting it from home.

Another thing that distinguishes the new museum is that we understand psychedelic video art as a mindstate dependent artform. It helps to be in a certain mindstate in order to fully appreciate these works of art. We don’t tell people how to get to this mindstate. Drug laws are obviously different from place to place. Some people can get there through meditation or other means, but definitely there is a strong connection between this artform and the psychedelic experience. These works benefit from full undivided attention, a contemplative gaze and even a certain level of ritual. It’s better to watch them on a big screen, with good speakers, and a willingness to let go and dissolve into them.

The new museum is a present for the world psychedelic community. It is non-profit, volunteer based, and designed to celebrate the beauty and richness of psychedelic creativity. On Sunday the 19th of April, at 3PM Eastern Time/8PM Greenwich Time, we will virtually convene to celebrate the 77th bicycle day, the tenth DPV anniversary and the launch of the psychedelic video museum in a psychomagical consecration ceremony which will move between various spots on the planet, open intergalactic gates, and including singing, dancing, speeches and occult rituals. A special psychedelic screening will take the viewers on a journey in a glowing land of psychedelic visuals. You are welcome to join us for the launch from home, and of course, come and visit and the Psychedelic Video Museum at any time you’d like.

This article was originally published in XXV edition of the Psychedelic Press Journal (2018) p. 49-59. See here.

What is it about psychedelic visuals that makes them so arresting and absorbing? In Heaven and Hell Aldous Huxley argued that the arresting qualities of psychedelic visuals derives from their relation to mythic and preternatural realms of the mind. Many of the ancient mythologies (e.g. Greek, Celtic, Japanese, Hindu), Huxley noted, imagined and described the other, divine realms of heaven and the afterlife as realms of intensified color and light, as well as extraordinary visual beauty and harmony. These are places filled with gems, shining stones, or colorful flowers. Ezikel’s version of the Garden of Eden is filled with such luminescent gems. The New Jerusalem is constructed in glimmering buildings of shimmering stone. Plato’s world of the ideals is described where colors possess a purity and brilliance absent from their real-world manifestations.[1]

[An example of mutli-perspectivism in psychedelic video. Jeu]

Our fascination with gems, shimmering objects, colorful flowers, and translucent stained-glass windows stems from their resemblance to the glowing beauty gleaned in the visionary’s inner eye, argued Huxley. By viewing such objects of beauty, we are reminded of the visionary realms and can be transported into them.[2]

Huxley’s ideas about the ways in which visual perception and aesthetics underlie the mystical experience and define its features have provided some of the background to a web project I’ve started eight years ago, dedicated to the exploration of psychedelic video aesthetics. The Daily Psychedelic Video began with the simple premise of creating a daily stream of curated psychedelic videos. It started out as an individual effort but quickly evolved into a group blog, representing the tastes of some 15 psychedelic video aficionados who have since contributed to the site.

Over these years, we’ve been cultivating a growing selection of psychedelic videos, one video a day (after eight years these have amassed to 3,000, making this the largest psychedelic video collection on the web), compiling video lists, and arranging psychedelic screenings. What I’ve learnt in this period inspired me to think not only about psychedelic aesthetics in themselves, but about their connection to both the natural and preternatural worlds, and to the processes and dimensions of psychedelic healing.

The relationship between psychedelic visuals and the psychedelic experience

Where does one begin an exploration of the aesthetics of psychedelic video aesthetics? Perhaps by noting some of their common characteristics. Beyond their lavish colorful qualities, and their effusive use of light, noted by Huxley, psychedelic videos have several recurring and defining characteristics. Among these are the preoccupation with (1) multi-dimensionality (particularly in the use of fractals, see for instance Cyriak’s Hurray for Earth video, or this extreme Mandelbrot fractal zoom) as well as with (2) multi-perspectivism (See for example in George Schwitzgebel’s Jeu, in Wild Child’s Rillo Talk video, or in Let Forever Be video by the Chemical Brothers), an (3) fondness to the use of mandalas, tunnels, kaleidoscopic imagery and other types of harmonious symmetries (Busby Berkeley provides some examples from the 1930s, a video titled ‘L’illusion de Joseph’ does the same based on 19th century phenakistoscope images), and (4) perhaps most uniquely to the video format, a proclivity towards the exploration of flow, fluidity and shifting contours and shapes (see for instance this meditative video of the ocean waves, this video by Nihls Frahm, or this one by Liquid stranger, the Love and Theft video by Studio Bilder, or this bird watching video). Finally, (5) psychedelic videos often showcase distinct synesthetic qualities which are arguably less common in other psychedelic media. Synesthesia—the mixing of senses, as in the seeing of sounds or the hearing of colors—is a common feature of the psychedelic state. In media that involve one sense only, such as paintings or music, synesthetic qualities are habitually implicit only. The music video genre, by contrast, is based on the combination of video and sound, so that it is, in a sense, inherently synesthetic. Psychedelic videos often draw on and develop these synesthetic qualities as seen in this captivating example by Andrew Thomas Huang or in many of the other examples above.

[Observe the use of multi-dimensionality in this psychedelic video by Cyriak]

Psychedelic mental and ideational phenomena, in other words, are reflected in their visual effects. It is perhaps because of this close relation between psychedelic visual phenomena and the ideational phenomena of psychedelics that psychedelic videos are able to recreate some of the disorienting, but also the harmonizing and healing effects that psychedelics tend to bring about.

The therapeutic language of nature and mathematics

How should one go about exploring the features and meanings of psychedelic video aesthetics? Unfortunately, works on psychedelic aesthetics have generally been few and far between. The fields of art studies and aesthetics have generally neglected to consider this area, concomitantly to their general disregard of the genre of visionary art. And while the last decade saw some renewed interest in psychedelic aesthetics (one reviewer spoke of a “psychedelic ‘turn’ in art criticism,”[6] a grossly exaggerated claim, in this author’s opinion) scholarly explorations of psychedelic videos are even more incipient than their equivalents looking into psychedelic art and design. A search of the literature was unable to produce even one paper dedicated to the subject of psychedelic video, their features, or properties. A remarkable state of non-knowledge. Moreover, it is unclear where exactly such a discussion would take place: a comprehensive view of this phenomena would need to consider not only the perspectives of art and aesthetics, but also those of cognitive psychology, evolutionary theory, religious studies and even computational theory, as I show below.

One possible entry point that might provide context and insights to the study of psychedelic aesthetics can be found in the domain of sacred geometry. Granted, the notion of a ‘sacred’ geometry seems remarkably out of sync with trademark academic language. Indeed, sacred geometry is not an academic field of study (though it has been the object of some academic attention). Nevertheless, the geometrical and natural patterns which it explores have fascinated philosophers, artists and mathematicians since millennia, capturing the attention of such varied luminaries as Pythagoras, Fibonacci and Leonardo de Vinci.[7] The ancient Greeks saw form and natural patterns as essential to the universe, part of a universal science which underlies the whole of reality. Naturalist scientists have long directed their attention to the harmonious mathematical ratios that are ubiquitous in nature: in the structure of crystals and snowflakes, the growth of ammonite, the vortexes of water streams and the movements of clouds. These contemplative explorers of nature found common and recurring ordered structures and patterns (spirals, waves, branching trees, and most famously the golden ratio and its related Fibonacci series) on different scales of natural phenomenon from conches and flowers to storm formations and galaxies.

[The use of symmetric patterns such as fractals and mandalas can already be observed in this 1930s video by psychedelic choreography maverick Busby Berkley]

In psychedelic videos we can observe many of the harmonious patterns and structures unveiled by earlier observers of nature and its patterns. Nevertheless, an additional element is present – an added dimension of dynamism, movement and unfolding. This element, of course, derives directly from the reality of nature, where things not only assume certain mathematically harmonious patterns, but also move in mathematically harmonious ways.

This dimension of movement and fluidity, which is absent from visionary and psychedelic art, but present in psychedelic video, is crucial to the meditative and visionary experience, which is not static but dynamic. Humans are naturally drawn to observing the movement of the clouds, the water in a stream, or the flames in a fire. In the psychedelic state our preponderance upon these natural phenomena seems to increase multifold. Psychedelic voyagers have been known to enter deep states of absorption while observing clouds, flames, streams or trees moving in the wind.

The pleasure we derive from watching these patterns of movement unfold in natural phenomena has more than just aesthetic implications. As anybody who has spent their time attentively observing such phenomena might recognize, they can have calming, soothing and even healing effect. Philosophers and naturalists have long sought inspiration and healing in the observance of nature and its patterns. Following various contemplative traditions which argue that when we are truly absorbed in the contemplation of an object, our minds become indistinguishable from the thing, it is easy to see how the creation of inner calm and harmony can be assisted by taking in external manifestations of such harmony and consonance. By observing the ratios and proportions of nature we are, in a sense, aligning our minds with perennial cosmic laws that bring order, solace and satisfaction to the mind. This recognition is part and parcel of countless religious and spiritual traditions. Religious structures such as mosques, temples and cathedrals utilize the proportions and patterns of sacred geometry to inspire awe and religiosity in their visitors.[8] Taosim teaches the art of Feng Shui, which aims to inspire harmony within one’s personal dwelling place. This principle of using external harmonious structures to inspire inner harmony can also be found in entheogenic religions, which pay homage to the principles of set and setting, and to the notion that a well-arranged physical setting is paramount to inspiring inner calm and harmony. The Santo Daime entheogenic religion utilizes sacred geometry in the arrangement of space, as well as in the arrangement of the table (mesa) to which participants are called upon to direct their attention in the search of inner harmony.

[Observe the synesthetic qualities of psychedelic video, in this extraordinary example by Andrew Huang]

“Nature is data” as one gifted psychedelic video artist and mystic once put it to me. By watching the movement of clouds, streams, flames and tress in the wind, we are able to directly observe in physical form the universal mathematical laws that move creation. These laws that move things exist on many different scales and levels, from the conch and the flower, to storms and galaxies, but presumably also in computer algorithms, the movements of the stock market and other man-made phenomena. These perennial relations, ranging from the miniscule to the gigantic, and from the natural to the man-made, are held together by the language of physics and mathematics that permeates the cosmos and directs its movement. Digital physics has long promoted the idea that the universe could be seen as a sort of gigantic digital processor, computing some irreducible mathematical/evolutionary problem, with each electron in the universe representing a singular bit, in a what could be viewed as a cosmic computer.[9] Even ocean waves with their countless streams and splashes could be viewed as calculating some irreducible and inconceivably complex problem that our most advanced devices and processors would be grossly incapable of precisely measuring or computing.

Many works of psychedelic video utilize these natural patterns and mathematical formulas of change to inspire joy and awe in their viewers. The same features of the harmonious movement of a branch in the wind, or seaweed in the stream, can be found in many of the psychedelic videos that observe or imitate the flowing harmonies of nature. By viewing these perennial ratios and patterns on the screen we are transported and able to connect to inner sources of order, harmony and healing.

If psychedelic videos can inspire deep states of joy and healing, as I have observed them do countless times in private and public screenings, then their significance transcends the purely aesthetic and becomes therapeutic. As noted above, the principles and practices of set and setting — the idea that the context of psychedelic experimentation shapes its content — encourage us to search for suitable forms (physical or otherwise) that might provide supportive and inspiring context for psychedelic experiences. In the same way that art and artistic reproductions have been used in psychedelic therapy from its inception,[10] meditative video aesthetics can be used as part of therapeutic processes. Moreover, such mind-transforming videos might prove to have measurable and potentially useful psychological and physical effects on their viewers in and of themselves.

[Fluidity is another key characteristic of psychedelic videos. The video Infinite Now demonstrates spectacularly]

Understanding psychedelic video might prove instructive and useful not only for the fields of art, aesthetics and therapy. Psychedelic video aesthetics might prove to be a worthy object of investigation for other areas including cognitive science and evolutionary theory. The human propensity to observe, become absorbed and find satisfaction and solace in certain recurring, mathematically-patterned, aesthetic phenomena, offers a phenomenon worthy of the attention of those interested in understanding human cognition and its evolutionary roots. Where does our fascination with such ordered forms come to? How do they bring alterations of body and mind? What can they teach us about the way our mind and its interactions with the world?

Towards a science of psychedelic aesthetics

So what prevents the study of psychedelic or meditative video aesthetics from becoming a field? The inertness of research on the subject is particularly curious when contrasting it to the growing scientific interest in other comparable cognitive phenomena such as the perception of cuteness. Over the past years, a growing field of research extending from psychology and evolutionary science to neuroscience and cultural studies has come to focus on human perception of cuteness, producing hundreds and thousands of scientific papers. This research identifies on recognizing the distinct physical traits that facilitate the perception of cuteness (such as large eyes, bulging craniums and retreating chins), but also on its evolutionary sources (the need to ensure parents care for their offspring), behavioral reactions to cuteness, and its hormonal, genetic and neuroscientific substrates.[11]

The study of cuteness presents a possible model for the study of psychedelic video aesthetics. Unfortunately, this task has not yet been undertaken by any of the relevant academic disciplines, and this ignorance and peculiar incuriosity is accentuated by comparison with the wealth of interest and attention afforded to phenomena such as cuteness. It is time we started to study the universal and perennial forms of beauty and grace that are ubiquitous to human experience, nature and the arts, and which are equally omnipresent in psychedelic experiences and aesthetics. By studying such phenomena, we can advance not only our appreciation of the human mind, its development and proclivities, but also come across new methods and techniques with potential life-enhancing value of optimizing therapy and conducing the healing of the psyche.

[1] Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception & Heaven and Hell (NY: Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2011).

[2] Huxley.

[3] Heinrich Kluver, “Mechanisms of Hallucinations,” in Studies in Personality, ed. Q McNemar and M.A. Merrill (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1942); Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff, Beyond the Milky Way: Hallucinatory Imagery of the Tukano Indians (UCLA Latin American Center Publications, 1978); James L. Kent, Psychedelic Information Theory: Shamanism in the Age of Reason (CreateSpace, 2010).

[4] See for instance Philip K. Dick, VALIS, Reissue edition (Boston: Mariner Books, 2011); Stanislav Lem, The Futurological Congress: From the Memoirs of Ijon Tichy, 1 edition (San Diego: Mariner Books, 1985); and also the work of Huxley and Leary on the concepts of reducing valves and reality tunnels covered in Ido Hartogsohn, “Psychedelic Society Revisited: On Reducing Valves, Reality Tunnels and The Question of Psychedelic Culture.,” ed. Robert Dickins and Andy Roberts, Psychdelic Press 2015, no. IV (August 2015): 83–99.

[5] Terence Mckenna, The Archaic Revival: Speculations on Psychedelic Mushrooms, the Amazon, Virtual Reality, UFOs, Evolution, Shamanism, the Rebirth of the Goddess, and the End of History, 1st ed. (San Francisco, CA: HarperCollins, 1992); Katherine A. MacLean, Matthew W. Johnson, and Roland R. Griffiths, “Mystical Experiences Occasioned by the Hallucinogen Psilocybin Lead to Increases in the Personality Domain of Openness,” Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 25, no. 11 (November 2011): 1453–61, https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881111420188; Matthew M. Nour, Lisa Evans, and Robin L. Carhart-Harris, “Psychedelics, Personality and Political Perspectives,” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 0, no. 0 (April 26, 2017): 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2017.1312643; Taylor Lyons and Robin L. Carhart-Harris, “Increased Nature Relatedness and Decreased Authoritarian Political Views after Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression,” Journal of Psychopharmacology, 2018, 0269881117748902; Robin L. Carhart-Harris et al., “Neural Correlates of the LSD Experience Revealed by Multimodal Neuroimaging,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, no. 17 (April 26, 2016): 4853–58, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1518377113.

[6] Orit Halpern, “Psychedelic Vision,” BioSocieties 8, no. 2 (June 1, 2013): 239, https://doi.org/10.1057/biosoc.2013.11.

[7] Stephen Skinner, Sacred Geometry: Deciphering the Code (Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2009).

[8] Skinner.

[9] Stephen Wolfram, A New Kind of Science, 1 edition (Champaign, IL: Wolfram Media, 2002); David Deutsch, The Fabric of Reality: The Science of Parallel Universes–and Its Implications (Penguin Books, 1998).

[10] Betty G Eisner and Sidney Cohen, “Psychotherapy with Lysergic Acid Diethylamide,” Journal of Mental Disease, 1958, 127 (1958): 528–39; Timothy Leary, George Litwin, and Ralph Metzner, “Reactions to Psilocybin Administered in a Supportive Environment,” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 137 (1963): 561–73.

[11] See for instance Morten L. Kringelbach et al., “On Cuteness: Unlocking the Parental Brain and Beyond,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20, no. 7 (2016): 545–558; Melanie L. Glocker et al., “Baby Schema in Infant Faces Induces Cuteness Perception and Motivation for Caretaking in Adults,” Ethology 115, no. 3 (2009): 257–263; J. W. S. Bradshaw and E. S. Paul, “Could Empathy for Animals Have Been an Adaptation in the Evolution of Homo Sapiens?,” Animal Welfare 19, no. 2 (2010): 107–112; Douglas Watt, “Toward a Neuroscience of Empathy: Integrating Affective and Cognitive Perspectives,” Neuropsychoanalysis 9, no. 2 (2007): 119–140; R. Sprengelmeyer et al., “The Cutest Little Baby Face: A Hormonal Link to Sensitivity to Cuteness in Infant Faces,” Psychological Science 20, no. 2 (2009): 149–154.

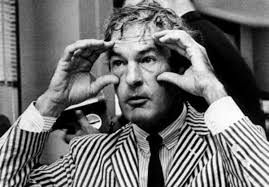

Yesterday evening I had the great privilege and honor of hosting Rick Doblin, founder and executive director of MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies) at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, as part of an event organized by the Harvard STS Program. Rick, whose been leading the effort to bring MDMA into a medicine since the 1980s is also a Kennedy School alumnus. He graduated from HKS in 2001 with a dissertation on the regulation of the medical uses of psychedelics and marijuana. Rick can be considered an exemplary alumnus for an institution such as HKS which is dedicated to educating and empowering public policy reformers: he has been a key figure in bringing about a huge and long awaited public policy revolution — the renewal of psychedelic research, and the medicalization of psychedelics. It was for this reason among others, that it felt particularly meaningful to bring him back to HKS.

The event was titled “The Altered Mind: Psychedelics & the Ethics of Mind-Enhancement.” It sought to adumbrate and discuss the social, political and ethical questions surrounding the resurgence of psychedelic research (see the abstract here). Apart from Rick we also had an excellent panel, which included Harvard Prof. bioethicist Dan Wikler, as well as New School Anthropology Prof. Nicolas Langlitz and myself. The whole thing was moderated by Prof. Sheila Jasanoff, director of the STS program at Harvard.

Here is a transcription of my response to Rick Doblin’s presentation, which explores some of the intersections between drug discourses and normativity.

***

Thank you all to coming to this event which was intended to invoke some of the fundamental and rarely asked questions surrounding psychedelic research and drug research in general.

I want to continue on some of the issues and questions that were raised by the previous speakers and include them within an even broader discussion which I believe we should be having about the normative issues framing psychedelic research and medicine.

Before we go into that, it should be noted that drug laws and regulations have been regularly and intimately shaped by questions of normativity. There is rich historical and sociological literature that details the many ways in which anti-drug campaigns and drug laws have historically been inextricable from racism and the persecution of racial, cultural, and political minorities: In the case of marihuana these were Mexican immigrants, Chinese immigrants in the case of opium, black people in the case of cocaine. In each of these cases, anti-drug campaigns were accompanied by strong sentiments of racial belligerence, opposition to minority groups and to the social values associated with these groups.

The case of psychedelics was not different, though admittedly the persecuted group here was not a racial group but a cultural and political group which included hippies and political radicals.

Back in the 1960s psychedelic use was strongly associated with specific cultural and political trends such as pacifism, opposition to the war in Vietnam and anti-authoritarianism. Psychedelics were widely understood by their users, as well as by their detractors, to be drugs which foment opposition to certain cultural norms including consumerism, materialism, nationalism and the work-ethic. They were considered to undermine the very normative and ideological foundations of civilization. Many of their users saw them as harbingers of a new kind of society. “Present social establishments had better be prepared for change” Timothy Leary argued at the time. He predicted that mind-altering drugs would radically transform human nature and society.

Leary’s attempt for a psychedelic cultural revolution did not lead to the expected results, and over the past couple of decades, the story of the so called ‘psychedelic renaissance’ has been inextricable from the trend of ‘mainstreaming psychedelics,’ the distancing of psychedelic research from its earlier associations with the counterculture and political radicalism.

Rather than transforming society through countercultural activity, later day psychedelic advocates agreed that the better route goes from within the culture. After suffering from their association with 1960s political discord and strife, psychedelic advocates vied to bring them back as a bipartisan issue, which I think explains some of the issues that were raised here today regarding psychedelic research and its connections to conservative groups.

Psychedelic activists of the 1960s burned draft cards, but those of the 21st century provide therapy to Army veterans and this must be seen as part of an effort to rehabilitate psychedelics in the public eye and change their image from drugs which challenge the social order to drugs that seek to ‘heal’ it, as some psychedelic advocates would say, or perhaps even support it, as others might say.

At the same time, psychedelic research is still associated and to some extent dependent on a broader community with distinct cultural resonances. This wider group, which meets together at conferences and events, still provides financial, moral and cultural support for the cause of psychedelic research. The big question for the members of this culture is whether the benefits of the medicalized mainstreaming of psychedelics justify the normative costs. In other words: to what extent does entering the scientific and medical game dilute what members of the community perceive to be fundamental, core psychedelic values.

While many advocates argue that medicalized discourse falls short of doing full justice to the more radical sociopolitical implications of psychedelics, in most cases the community surrounding these agents has been overwhelmingly supportive of the contemporary wave of research. The subjection of psychedelics to the analytic gaze of science is considered a necessary step for gaining scientific recognition of their merit and securing their future availability. This, in spite the fact that many users and advocates consider legal access to psychedelic therapy and experimentation an inalienable human right. This idea of psychedelics as a human right is justified and expressed either through reliance on anthropological data about the historical ubiquity of psychoactive use in human societies, or in the language of cognitive liberty – the assertion that the right to alter one’s state of mind according to one’s wishes is tantamount to the right to free speech.

So far, I’ve described the mainstreaming approach and its reception from within the psychedelic community. Rick has been a chief proponent of this approach, which argues that the value of psychedelics can be recognized by all sides of the cultural and political map. And yet, at the same time psychedelics are also promoted as fostering certain kinds of values which in today’s political climate seem to relate quite clearly to a specific part of the political landscape. Psychedelics have been widely proposed to promote values of eco-awareness, universalism, anti-authoritarianism, tolerance and openness. The question of whether and how comfortably these values sit together with the mainstreaming of psychedelics, and whether the political implications of psychedelics might subvert their bipartisanship remains unsettled in my eyes.

If we assume that there exists a relationship between drug laws and normativity: that psychoactive drugs which alter minds help produce certain types of societies, and that drug norms and laws are shaped by the agreement or disagreement, between the values held by society, on the one hand, and the values associated with certain drugs, on the other hand – then we might assume that it is not per accident that the drugs most in use in late capitalist society are drugs which have been described as drugs of productivity and adjustment such as caffeine, Ritalin, Adderall, Zoloft and Prozac.

One useful distinction in this regard is made by communications professor Corey Anton who speaks about two archetypal types of drugs. The first type is tight drugs, which help their users become more attuned to the demands of society, without causing any dramatic perceptual effects. The second type are loose drugs, which explicitly alter consciousness and free individuals from the grip of normative values. By contrast to the tight drugs which fuel civilization, the psychedelic experience, has been popularly associated with changes and challenges to social values.

The question of whether this is indeed the case, remains open to debate. There is evidence to suggest that psychedelic experiences promote free thinking and liberal values, but there is also historical and ethnological data about groups who used psychedelics while engaging in sorcery, war and human sacrifice; and although predominantly identified with leftist politics, psychedelics have also had some supporters from the right.

I would argue that psychedelics might indeed support liberalization, but that their exact social effects depend on the set and the setting, or the context in which these drugs are being used. Psychedelics can be used to liberalize, individualize, and radicalize, but they can also be used to strengthen communal structures and values, as shown by ethnological research.

The return of psychedelic research therefore presents us with a question regarding the kinds of values society wishes to espouse. We already have legally sanctioned use of drugs to enhance productivity and facilitate adjustment to society’s values. Are we willing to approve drugs that are assumed to promote social values such as openness, tolerance and opposition to authoritarianism? And if, on the other hand, we assume that it is set and setting that shape the normative effects of psychedelics, what kind of set and setting do we put in place to determine the types of values that psychedelics end up promoting?

These are a few of the issues that I see coming up, and which, to my mind, underscore the crucial normative questions that any discussion about the social role of psychoactives in general and psychedelics in particular must take into account.

Beyond running a couple of internet blogs dedicated to psychedelic culture, in my spare time I also do academic work in the field of psychedelics. This past year I’ve had a chance to bring psychedelics to Harvard, where I’m now a visiting postdoc (and if you’re around the Boston area, this Wednesday I will be organizing an event that will bring MAPS founder and executive director Rick Doblin to this Alma Mater, the Harvard Kennedy School, on the 28th of March, at 4PM).

Two weeks ago, a new paper of mine was published in a special issue of Frontiers of Neuroscience, edited by psychedelic research pioneer Rick Strassman, and dedicated to the subject of psychedelic medicine. My new paper, “The Meaning-Enhancing Properties of Psychedelics and Their Mediator Role in Psychedelic Therapy, Spirituality, and Creativity,” continues on the path laid out by my two earlier papers: “Constructing drug effects: A history of set and setting,” (2017) and “Set and setting, psychedelics and the placebo response: An extra-pharmacological perspective on psychopharmacology” (2016). Both those earlier papers explored the issue of set and setting – the contextual factors (such as personality, expectation, intention and physical, social or cultural environment) which shape psychedelic experiences. The first paper looked at the history and evolution of the concept of set and setting since the 19th century, while the second one examined the relationships and correlations between the concept of set and setting and that of placebo, and how considering these two concepts in conjunction might enrich our understanding of both set and setting and placebo.

My new paper discusses the importance of meaning enhancement in psychedelic experience. While the words set and setting are not in the title this time, this is nevertheless a further development of the two earlier papers. Set and setting is critical for psychedelic experimentation because meaning is augmented and intensified by psychedelics so that any minimal cue can be radically amplified —whether positive or negative— leading to the “heaven and hell” character of these substances, as Aldous Huxley put it. In my new paper I argue that this meaning-augmenting effect of psychedelics might be their most important one and look at the ways in which the meaning-augmenting aspects of psychedelic action facilitate psychedelic therapy, spirituality and creativity. The paper is open access so you can read it here in full.

I’m not a big expert on the chemistry of psychoactive drugs, but last week I had the opportunity of examining the structural formulas of common psychoactive molecules and was greatly amazed and amused. On the one hand, the structural formulae of chemicals are based on writing conventions that have nothing to do with the actual chemical substance or its effects. On the other hand, the pictures of structural formulas of psychoactives give rise to surprisingly vivid imagery and associations, imparting some rather interesting impressionistic lessons on the effects of drugs.

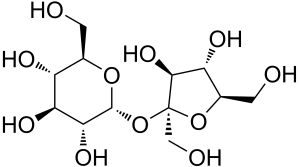

Sugar

Sugar looks like it’s currently in the midst of an ecstatic and jubilant dance, holding its own hands and swinging around in wild circles, rising to the firmament on the waves of glucose until it reaches terminal exhaustion. It is like a merry go round on which our whole culture is riding up and down.

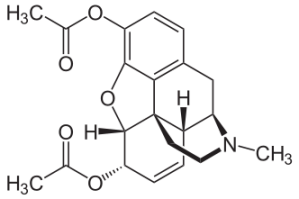

Heroin

By contrast to the joyous structure of sugar, heroin’s molecular structure appears like a train wreck – something that’s painful to look at. Heroin looks like two figures getting squashed one on top of the other, or forcefully clenching each other. Maybe the image points to addiction, which does not let go of the individual, and the individual who does not let go of their addiction. Or maybe it is the friend who is gripping the addict in support, telling them: “I won’t let leave you alone.”

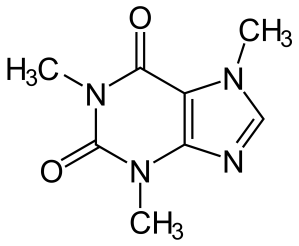

Caffeine

Caffeine seems like a very straight, even uptight character. Their head stands erect at the top of a long neck and they appear like a three-armed waiter, holding three trays with cups full of carbon and hydrogen atoms – always ready to be of service.

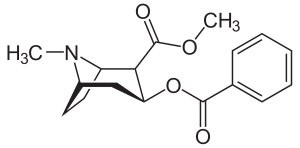

Cocaine

Cocaine looks like a scuba-diver with diving fins and a lever stuck up his behind. His head, on the right side of the drawing, is only tenuously and almost accidentally attached to his body, which is floating in space, and the expression on his face says everything, or nothing…

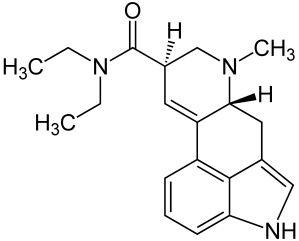

LSD

LSD looks like a caterpillar maliciously erecting itself on his hind legs. It has one scary, wide-opened eye that is carefully observing you and two evil antenna tentacles, with which it is about to attack you using hydrogen and carbon atoms, while you’re in the middle of a horror trip.

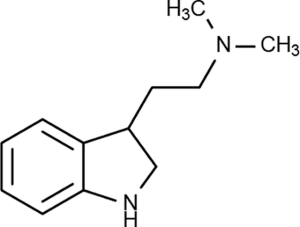

DMT

DMT seems like a mightily efficient creature without many superfluous organs. It weighs just enough so it can carry and hold up the key that opens the doors of perception.

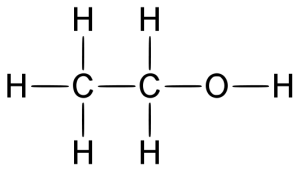

Alcohol

Alcohol looks like board meeting around a long, rectangular table in an alcoholic beverage company. It also looks like a two armed cross which has been laid on its side, and maybe it is our society’s religion, only skewed.

Recently I had the opportunity to talk on a popular Israeli TV show about the practice of micro-dosing on LSD. I was invited to the program as an expert on psychedelics, yet at a certain point in our conversation one of the hosts turned to me and asked. “Tell me Dr. do you yourself use LSD?” I was ready for this question, so I told him it would be better we’d discuss my practices after the show, however I wasn’t ready for his response. “Oh, is this because of the legal implications? Are you worried you’ll have cops waiting for you when you exit the studio?”

How do you answer a question like that? Certainly, part of the reason not to speak about psychedelic experiences on TV is because astonishingly they are still prohibited by law and publicly speaking about them might get one into trouble. Yet was the question even legit? Would the same TV presenter feel equally justified in asking a sexologist on the show, “So tell me Dr? Do you personally have lots of sex?” “Oh, would you rather not discuss this on TV because you are worried what our viewers might think?”

There wasn’t really anything unusual about this TV presenter’s questions. Actually, I had come to expect this kind of approach when I am interviewed about psychedelics. Yet the experience did lead me to think about the unique situation in which the discourse about psychedelics currently finds itself. While other political minorities such as the feminist, LGBT, or black rights movement have made great strides over the past decades, the psychedelic movement is still stuck somewhere in the 1960s, a time when racial segregation became illegal, homosexuality ceased being a crime and feminist consciousness soared – but experimenting with psychedelics became illegal and punishable by law. Since the rise of the minority rights movement it has become increasingly unacceptable to stigmatize women, LGBT, blacks and other disadvantaged groups, yet as “Stoner sloth”, the recent anti-weed campaign against weed reminds us, it is still accepted as perfectly legitimate, even desirable, to stigmatize drug users and paint them as dumb and lazy. In a world where disadvantaged groups are ever more vigilant about microagressions, it is still considered safe to debase drug users using derogative terms, portray them as recklessly irresponsible fiends, and blame them the ills of society. This happens although various reports have shown that stigmatization of drug users leads to discrimination, lower addiction-recovery rates, and even torture and abuse. The legal persecution of drug users makes things ever more complicated, deterring many from raising their voice against the demeaning stereotypization of drug users for fear of being stigmatized themselves.

But what if it became clear that there is a need to be vigilant when speaking about drug users as when speaking about other disadvantaged groups, and that the discrimination and persecution of drug users are another form of minority discrimination?

The identity politics of psychoactives

Adding psychoactive drugs to the discussion about minority rights is a risky undertaking. To start with, many have difficulties recognizing drug users as a minority group. Indeed, while the majority of citizenry is composed of drug users (certainly if one includes alcohol or coffee), drug users hardly ever identify themselves as a group. At the same time, minority activists themselves might revolt against the idea, reminding us that gender and race are biological realities, whereas drug preferences are not. Still, some support for the way the politics of consciousness might fit into the greater discussion about minority politics might be found in the acceptance of LGBT as an identity, although some have claimed sexual orientation is but a choice. The Wikipedia entry on identity politics states that the term might refer to a variety of possible identities, based not only on race, gender and sexual orientation but also on ideology, nation, culture, information preference or even musical or literary preferences. In that case, might we not consider psychoactive preferences as something which relates to a person’s identity? In actuality, the tendency to experiment with altered states of consciousness is arguably as natural and ubiquitous as the need to experiment with sexuality. All human cultures, indigenous or modern, make some use of mind-alterants, a tendency which often emerges already in childhood. Some people have a special propensity for experimenting with altered states of minds – yet they are not dumber, more dangerous, or in any way inferior to those who do not share this tendency, as is often suggested by anti-drug organizations.

The rapidly growing discourse on identity politics is fraught with discussions about privileged and discriminated groups, in which certain groups are acknowledged to be privileged over other disadvantaged groups. However, nobody speaks of the privilege of being able to use a favorite substance without fear of police violence and incarceration. Since the use of any drug necessarily also entails a lifestyle (consider, for example, the differences between alcohol, cannabis and coffee cultures) privileging some drugs over others is fundamentally privileging some types of cultures over others, and historically the drugs being privileged were those sanctioned by privileged groups, while prohibited drugs have been those used by marginalized groups. Marihuana was outlawed as part of a racist campaign which targeted Mexican immigrants; opium as part of a campaign against Chinese immigrants; cocaine in a scare campaign which demonized black users and psychedelics as part of a campaign to subdue the 1960s counterculture. The current war against drugs is also heavily mixed with race politics as evidenced by the fact that while 5 times as many whites use drugs, African Americans are 10 times as likely to be incarcerated for drug use. At the same time, sanctioned drugs, such as coffee, Ritalin or Prozac are those which are considered to allow the efficient management of human impulses and emotions for the optimization of economic production. Favoring some drugs over others is often favoring certain values over others. Being able to use your favorite drug without fear of incarceration is also a form of privilege.

Raising the consciousness about consciousness

Are the politics of consciousness a form of identity politics? The answer is far from simple, and yet, half a century after the beginning of the war against drugs and the rise of awareness to the unacceptable role that certain modes of speaking play in the discrimination of marginalized groups, it might be time for drug users and legalization advocates to learn a lesson in consciousness raising by embracing their identities and demanding a discussion about drugs which is free from stereotypes, debasement and dehumanization.

Update 10/07/2016

Psymposia have recently run an excellent series on psychedelics and identity politics which resonates and expands on the questions explored here. Check it out here.

This essay was originally published in the August 2015 edition of Psychedelic Press UK. It continues the exploration of some ideas which were discussed in an older essay which was published in this blog under the title “Culture is not your friend: on the countercultural ideology of psychedelic thinkers.”

Some thirty years ago, in May 1983, Terence McKenna’s contact lenses failed him during a critical moment of his speech at the psychedelic conference in Santa Barbara. Unable to read from the page, McKenna had to resort to improvising. Listening to the recording after the event, he couldn’t help but notice the crowd’s reaction to a certain bit in his improvised talk, when he’d spoken the words “psychedelic society”. He had never used the phrase consciously before, but hearing the ripples that went through his listeners when he brought up the concept made McKenna wonder about its possible meanings.

A year later, in a classic June 1984 talk which was given at the Esalen Institute, and later adapted into a chapter in the 1997 psychedelic anthology Entheogens and the Future of Religion, McKenna proposed some of the possible characteristics and implications of such a psychedelic society.[1] A psychedelic society, he suggested, need not be one in which all members ingest psychedelics themselves. Rather, it is a society which orients itself and lives in the light of the irreducible Mystery of Being; a society in which problems and solutions are displaced from their traditional central role, and which puts “irreducible Mysteries” in their stead. Such a society, McKenna suggested, would be less keen to find clear and definitive answers, and more open to exploring reality without imposing simplified structures upon it. It would be more immune to the disastrous urge for simple clear-cut answers and identities, which characterizes human societies, and more open to co-existing with the doubts and contradictions inherent to the cosmos.

McKenna’s vision of a psychedelic society was closely related to another of his most popular ideas: the idea that culture and ideology are not your friends. According to McKenna, ideology and culture are tools which give other people the power over one’s experience and identity, since they lead individuals to shape their identity according to pre-conceived forms. If you identify yourself with brands or with the popular ideas about what is beautiful, true, right or important, you are giving away the power over your experience to other people. You let others tell you what to think, instead of thinking for yourself.

Not to mistake culture and ideology as your friends meant seeking to understand reality in one’s own terms instead of buying into pre-packaged ideological and cultural deals such as communism, capitalism, democracy or totalitarianism. Psychedelics were the tools that would enable that to happen, for as McKenna repeatedly argued, psychedelics are boundary dissolvers, belief breakers, deconditioning agents which raise doubts in you whether you are a Hasidic Rabbi or a Marxist anthropologist.(Mckenna, 2012, p. 61) “The plants … don’t address cultural values, they blast through them, they address the animal body, the mammalian brain.”(“Terence McKenna – ‘Culture and Ideology are Not Your Friends,’” n.d.) The psychedelic human being was thus to be a person that creates his own culture and ideology. The psychedelic artist was to be the artist whose work is uniquely original, transcending the limits of pre-conceived styles and forms. The psychedelic thinker, the one thinker to think outside the established norms of thinking.

And there was another, even more fundamental, flaw to culture and ideology. Belief in itself, argued McKenna, was limiting to the individual, because every time you believe in something you are automatically precluded from believing its opposite. By believing something, you are virtually shutting yourself from all contradictory information, thus once again performing the sin of imposing a rigid simplified structure upon a infinitely complex reality.[2] A psychedelic society, McKenna suggested, “would abandon belief systems for direct experience.”(Mckenna, 2012, p. 58)

Reading the Psychedelic Society many years ago, in a time when I immersed myself in the universe of McKenna’s writings and talks, I was captivated by the idea. Yet in the years to come my thoughts of the subject have become less certain and unequivocal. Like many of McKenna’s ideas, the concept of the psychedelic society as a society without belief and ideology was a brilliantly articulated and inspiring notion, yet it seemed to have a suspect air of unexamined utopianism. Was it possible to live without culture and ideology? Was a society without certain types of shared beliefs and constructs even conceivable? In this essay, I wish to convey some of my thoughts and reflections on the subject following a recent encounter with a Spanish psytrance tribe.

A genealogy of the psychedelic counter-cultural idea

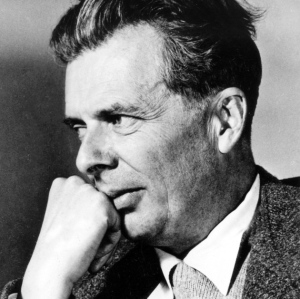

His Mind at Large theory was a philosophical precursor for McKenna’s psychedelic society. Aldous Huxley.

McKenna’s notions that culture and ideology are not your friends, and that belief is intrinsically limiting, were closely related to two other key ideas in the history of psychedelic thought: Aldous Huxley’s Mind at Large Theory and Timothy Leary’s idea of Reality Tunnels. Huxley’s Mind at Large Theory, elaborated in the Doors of Perception, suggested that Man’s view of reality is limited by a “reducing valve” which filters out his perception of reality so that it includes only the thinnest trickle of perceptions necessary for his survival. The function of consciousness, Huxley argued, following such thinkers as French philosopher Henry Bergson and the English epistemologist and philosopher C.D. Broad, was not to channel the myriad impressions perceived by the senses into our awareness, but rather to filter out the staggering noise of details which fills our raw perception. Consciousness was the mechanism which allowed us to edit out of our awareness the sound of birds chirping in the background while we are working to complete an important task; or making us neglect to notice the special way in which light reflects upon the skin of an apricot we are about to consume.

Were we to become engrossed in the many details perceived by the senses, we might become unable to function efficiently, Huxley argued, so consciousness edits out from our experience what it considers inconsequential information. In this way, an infinite world is reduced into our finite and more manageable, but also infinitely poorer and incomplete perception of reality: what we call a worldview.

Same as with McKenna’s culture and ideology, Huxley’s reducing valve was a mechanism which cuts down on the complexity of reality by fitting it into pre-conceived forms which make us more immediately efficient in terms of evolutionary survival, but immensely less open, creative, and aware. And culture was also a type of reducing valve. “What we see through the meshes of this [cultural] net is never, of course, the unknowable ‘thing in itself’ … What we ordinarily take in and respond to is a curious mixture of immediate experience with culturally conditioned symbol.”(Huxley, 1963)

The extraordinary value of psychedelics, Huxley argued, lay in their ability to allow us to loosen this reducing valve of perception and let ourselves behold reality in a fuller, richer way, bringing us closer to the Mind at Large, the ultimate reality of things, and enabling us to revolutionize psychology, spirituality, education and society. Psychedelics were tools for “cutting holes in cultural fences … the most urgent of necessities.”(Huxley, 1963)

About a decade after Huxley suggested his Mind at Large concept, Timothy Leary proposed his own take on the idea: the concept of the Reality Tunnel. Same as Huxley’s reducing valve of perception before and McKenna’s Culture and Ideology concepts after, Leary’s reality tunnels, later further elaborated by Robert Anton Wilson in books such as Prometheus Rising,(Wilson, 2009) were a pre-composed pattern which limits and distorts the perception of reality by reducing complexity and options. A person’s reality tunnel would determine their perception of the world, editing out those bits of perception which do not fit their beliefs, while singling-out and enlarging those details which fit well together with the persons’ particular reality tunnel. A capitalist, for example, would avidly gather any fact and piece of information which might support their claim that capitalism is the best economic system, easily forgetting and discarding any piece of information which might contradict that view. Similarly, a sworn communist would avidly collect any article of information which might support their claim that communism is the best economic system, quickly forgetting and discarding any piece of information which might contradict that view. Reality tunnels were ubiquitous and included “Eskimo totemists, Moslem fundamentalists, Roman Catholics, Marxist Leninists, Nazis, Methodist Republicans, Oxford agnostics, Snake worshipers, Ku Kluxers, Mafiosos, Unitarians, IRA-ists, PLO-ists, orthodox Jews, hardshell Baptists etc. etc.”(Wilson, 2009, p. 169) All of us harbor established ideas about minorities, religions, nationalities, the sexes, the right ways to think, act, feel, govern, eat, drink and what not. Reality tunnels act to help us fortify these ideas against any challenging information.[3]

Like Huxley’s reducing valve, Leary and RAW’s reality tunnels are a physical metaphor (a valve in the case of Huxley; a tunnel in Leary’s case) for mental “structures” which reduce an irreducible reality into the impoverished worldviews Man holds. The two concepts were both highly compatible with McKenna’s Culture and Ideology are not your friends. A subtle difference existed, however, in the main focus of each of these theories, and in the ways in which they were habitually framed. Whereas Huxley’s reducing valve metaphor was mostly concerned with how consciousness edits the impressions of senses into our perception, Leary and RAW’s reality tunnel concept was primarily concerned with how consciousness endlessly works to create ideological constructions and obstruct other possibilities from view. McKenna’s culture and ideology are not your friend argument, in turn, was primarily concerned with the ways in which external constructs imported by consciousness serve to limit not only our worldview but also our identity and our possibility to exist as unique, authentic beings.

Thus, as I have previously shown,(Hartogsohn, n.d.) Huxley’s reducing valve, Leary and RAW’s Reality Tunnels, and McKenna’s Culture and ideology are not your friends are basically different aspects of one the same idea – that the structures of the mind serve to limit our perception and experience of reality in a disempowering way, and that psychedelics are the antidote which allows us to dissolve these limiting structures and beliefs. If one might speak of psychedelic philosophy as a coherent body of thought, then this would certainly be one of its most basic tenets and features: the ideal of the psychedelic minded individual as a person who perceives and experiences reality in the fullest, richest, most flexible and least-prejudiced way possible, who methodically trains himself to loosen his reducing valve, who is profoundly aware of the limiting power of reality tunnels and ideologies and learns to avoid them or deal with them in conscious, intelligent ways. This idea, which has different variations in the thought of Huxley, Leary, RAW and McKenna can also be found in the work of later psychedelic and countercultural thinkers such as Douglas Rushkoff[4] and Erik Davis.(Hagerty, n.d.)

A society without a culture?

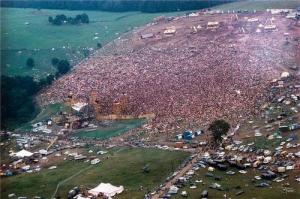

Was this a psychedelic society, or to the opposite, a betrayal of the idea of a psychedelic society. Woodstock, 1969.

In suggesting the concept of Psychedelic Society McKenna took a psychedelic and countercultural ideal, that of a unique life not given to pre-conceived cultural and ideological structures, and moved it from the personal to the societal level. In the same way that human beings should strive to live as free as possible from pre-given notions and ideas, so should society confront the world in the most creative and open-minded way possible without adhering to cultural structures.

As McKenna was fond of saying, quoting the British entomologist J.B.S Haldane: “The universe may not only stranger than we suppose. It might be stranger than we can suppose.”(Mckenna, 2012, p. 57) Our society’s tools for understanding the universe are limited by nature. Every culture in history believed that it got 95% percent of the world figured out, and that the other 5% will soon be in grip, argued McKenna. Modern culture, like so many before it, enjoys gazing back on the ideas of its predecessors with an air of ridicule, congratulating itself on finally getting it right. However, this claim was none the less ludicrous and parochial in our time than it was in the time of the pharaohs, and where was it even written “that semi-carnivorous monkeys can or should be capable of understanding reality?”[5]

A psychedelic society, by contrast, would be a society which doesn’t purport to have reality neatly organized by some popular ideology. Rather it would be willing to explore questions and possibilities. Such a society will, moreover, not just abstain from confining itself to one version of reality. Rather it would put the great mystery of being, the paradoxical, unfathomable nature of reality, at its very center.

Still, there seemed to be inherent dangers to the injection of idea that culture and ideology are not your friends into the social level. Culture, after all, stands at the basis of human society. It is the thing that emerges in any place where joint human life exists and it is difficult to imagine life without it. If one were to relinquish any form of culture, after all, one would have no art, no music and not even language, for what is language if not shared cultural constructions which inhabit the mind of the individual and shape it into a template which is unique to the culture. Ridding ourselves of ideology was an equally tricky thing to do. How would society function for example if we just stop believing in democracy and human rights? And after all, as one commentator noted, did not the culture and ideology are not your friend meme itself have a underlying thread of individualism, “a very western (especially North American) culturally based belief.”(Hartogsohn, n.d.)

It was not possible to throw away all of culture. As McKenna himself pointed out, there are some parts of it we wouldn’t want to discard, like the Sistine chapel, the Rembrandts, the Piero della Francescas and even the scientific method.(“Terence McKenna – ‘Culture and Ideology are Not Your Friends,’” n.d.) You didn’t want to throw out the baby with the water, and getting rid of a the whole of culture was moreover a highly risky business. McKenna’s point was that you wanted to spend as much time creating your own culture/ideology with you and your friends, rather than just consuming something created by somebody else. This, however, did not, could not, mean disavowing any type of shared cultural creativity. McKenna himself, after all, was a huge cultural buff, and an avid aficionado of various cultural artifacts such as the writings of James Joyce, Marshall McLuhan, and C.G. Jung, or the esoteric knowledge contained in the I Ching. Despite his tirades against culture, McKenna was an insatiable consumer of myriad forms of culture, which trickled into his thought and informed his ideas and thinking.

You still wanted to be able to keep at least some of what was good about culture, while editing out those parts of it that were useless and counterproductive. But how was one to accomplish such a task – a question all the more pressing in the absence of any ideology to guide oneself – is something that McKenna, to the best of my knowledge, never really answered.

There existed an inherent tension between the wish to purge humanity of the demons of culture and ideology, and the humble realization that by casting away these two we risk losing the very things that make us human: our ability to inhabit a shared mind-space, indeed the very conditions which allow us to co-exist as a society. McKenna argued that culture and ideology are not you friends, but he never went as far as saying that society is not your friend, even though it was not clear how a of society without any ideology or culture would look like.

***

Even though the terms and exact ways in which a psychedelic society would function remained vague, there seemed to be two fundamental ideas that would characterize such a psychedelic society. 1. It would live in the light of the great mystery of being. 2. It would seek to eradicate ideology and diminish the prominence of culture in a way that would allow for greater degrees of openness and creativity, as well as a more unique experience of being.

If there ever existed a society of the sort, then it might very well have been Kesey’s Merry Pranksters. Kesey, after all, was also the prototypical psychedelic leader, a self proclaimed non-navigator whose main function was to inspire and allow those around him to explore and lead themselves.

The direct, immediate and overpowering experience was at the center of Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, who were more interested in endlessly breaking boundaries than in reaching any final destination. As Kesey later said in an interview quoted in part six of Oroc’s Pyschedelic Revolution series to which I will come in the next part,(Oroc, n.d.)

The answer is never the answer. What’s really interesting is the mystery. If you seek the mystery instead of the answer, you’ll always be thinking. I’ve never seen anybody really find the answer, but they think they have. So they stop thinking. But the job is o seek mystery, evoke mystery, plant a garden in which strange plants and mystery bloom.(Faggen, 1994)

However, was it not telling that the Merry Prankster’s free-wheeling and anarchic ride across the united states also left a trail of acid and DMT casualties along the way, as the intrepid group continued it trip furthur and beyond? And even the pranksters arguably only existed as a truly psychedelic society for that short and adventurous period of time. Perhaps in order to exist as a psychedelic society without any cultural and ideological you needed to be in a state of constant revolution? Such a state is one which very few societies, if any, could maintain for a sustained period of time.

Confronting psychedelic culture in the Vega

In the spring of 2015, after a year in Spain, I arrived to my first Spanish psytrance party. The location of the party was south of Granada, in the hilly area known as the Vega. There had been some 100-200 psychedelic ravers in the event, a small and select gathering of the relatively small Spanish trance tribe, with plenty of old timers as well as dedicated young ravers.

What can a random meeting of psychedelic trance ravers teach us about psychedelic society? The Vega, near Granada, Span. 2015.

I had arrived to the party after a long period of psychedelic abstinence. The night before, I had read James Oroc’s sixth and final installation in the series on what Oroc calls the second psychedelic revolution (defined as the psychedelic movement that reemerged ever since the 1990s).(Oroc, n.d.) The ultimate chapter of this engaging series had been the most compelling and inspiring answer to the question of why psychedelics matter that I have encountered since McKenna’s Psychedelic Society. Oroc suggested that in an ego-obsessed society wildly and blindingly driving itself to its own mutually assured destruction, the rediscovery of the transpersonal experience and the interconnected of all things, and the breaking down the disastrous somnambulism of technological civilization, is humanity’s only chance for survival. The psychedelic perspective was the one required for humanity’s adaptation and survival, the antidote for humanity’s current position of aimlessness, blindness and general numbness.

The second psychedelic revolution, Oroc claimed, was actually part of a fifth cycle in a history of psychedelic cultures. This fifth psychedelic culture, the modern psychedelic culture whose roots can be found already in the discovery of mescaline at the end of the 19th century, followed four major sustained psychedelic cultures in history, which included Ancient Greece with its Eleusinian mysteries; Vedic India and its soma; Mexico’s Toltec, Mayan and Aztec cultures; and the ancient Chavin civilization of Peru.

Oroc’s bleak portrayal of the state of human civilization contrasted strongly with his view of this fifth psychedelic culture, which he described as exceptionally intelligent, tolerant and open-minded. A society with incredible creative resources, which is in the process of breaking out of the festival model in order to build permanent communities of responsible psychedelic users. “Responsible psychedelic use can build community,” Oroc insisted.(Oroc, n.d.) Yet another reason why psychedelic were so crucial too our culture.

And still, at the same time, Oroc seemed aware of the many pitfalls psychedelic culture is in risk of falling into, acknowledging a “growing move towards hedonism, escapism and a flirtation with the fantastic”, and confessing that even he was despairing at times “that the message is being lost in all the beautiful pictures and the pretty lights.”(Oroc, n.d.)

Arriving to the Vega psytrance party that weekend confronted me with the living reality of a psychedelic society in action – what it was what it wasn’t. Of course, one could not surmise that this specific event I half-randomly arrived to was representative in any way of the whole of psychedelic culture, yet somehow, by the virtue of its generic character, it actually did seem to represent much about the current state of psychedelics in culture and society.

Observing the event as an outsider to the scene, I could sense the community and it’s spirit – an manifestation of a society centered around the psychedelic experience. Psychedelic society, after all, was not only a theoretical concept discussed in Californian psychedelic conferences. It was also an actual way of life which emerges in various environments and conditions.