Yesterday I published a new piece on the Daily Psychedelic Video which deals with an intriguing topic: what type of new Reality TV formats might arise when psychedelic legalization comes?

Yesterday I published a new piece on the Daily Psychedelic Video which deals with an intriguing topic: what type of new Reality TV formats might arise when psychedelic legalization comes?

A few of the suggestions included in the article: A Psychedelic Big Brother show in which contestants stay dosed the entirety of the show, an Acid Survivor version and a psychedelic cooking show. Everything is presented in the spirit of humor and wild imagination, of course…

One of the positive side effects of psychedelics is their ability to improve one’s nutritional habits. In his book LSD: My Problem Child Albert Hofmann relates how extraordinarily his sense of taste was enhanced after his first LSD trip. The experience of great excitement one gets when biting into carrots or lettuce after a psychedelic experience — sensing their rich sweetness — is tantamount to eating for the first time after six days of fasting. Suddenly, each fruit and vegetable regains its original heavenly taste, as though we are experiencing, for the first time, the real taste of food.

Psychedelic Eating

Psychedelic experiences tend to change our relation to food in many other ways. Ayurveda and other spiritual traditions recommend performing a ceremony prior to eating: contemplating the source of your food, and giving thanks to it, for surrendering its vitality and life so that you can live on.

Psychedelic experiences tend to change our relation to food in many other ways. Ayurveda and other spiritual traditions recommend performing a ceremony prior to eating: contemplating the source of your food, and giving thanks to it, for surrendering its vitality and life so that you can live on.

Ayurveda also teaches us to dedicate our full attention to the food we are eating, in a manner befitting the act of sacrifice, while receiving the life of the food: not to talk while eating, not to watch television or read the newspaper; to eat in meditation and in concentration. Mindless eating is a sort of barbarism, like mindless murder.

Psychedelic experiences tend to change our relation to eating in a way parallel to that recommended by a number of spiritual traditions. Devouring food during a psychedelic experience, or shortly thereafter, bestows entirely new dimensions on the act of eating. I remember a special moment when, before consuming a grapefruit, I saw its glowing vivaciousness for the first time. I held it for minutes, which seemed like eternity, fondling it, inhaling its rich scent, feeling it alive and pulsating in my hand. I remember the moment of peeling its skin, which felt almost like a type of defloration — only much enhanced since our intercourse was totally unique, as it would happen only once, and end with our complete and irrevocable unification. The red flesh of the grapefruit was exposed for the first time to the light, and while I stripped away its skin, I intently watched its composition — tens of thousands of miniature succulent fruit pieces interlaced into what seemed like a huge crimson wing, composed of myriad translucent membranes.

That feeling of endless intimacy that I shared with that grapefruit is difficult to describe. I felt as though it was the first time in my life that I was actually seeing what I was putting into my mouth, and this tremendously enhanced the experience of eating.

I ate together with friends, and the act of sharing the food reminded me of the act of grokking, which Robert A. Heinlein so famously describes in his Stranger in a Strange Land. I was not only eating the food, I was becoming one with it. The concept of eating suddenly received its full significance — as a mystical ceremony, an act of uniting, a sacred deed accompanied by the categorical imperative to completely change and give full respect to the food that I eat.

Pyschedelic Nutrition

I do not mean to claim that every person who will use psychedelics will change his nutrition. Of course, you can use psychedelics and still eat indiscriminately. One of the common impulses after a psychedelic experience is to run directly to the nearest hamburger stand. You can fall victim to it once, or even for many years, but a serious user of psychedelics will often start receiving messages which call upon him to:

- Stop destroying the body with harmful nutrition. — Malignant nutrition is the continuation on a personal level of the ecological pollution caused by the human race.

- Stop taking the lives of others. — Develop a moral basis to your nutrition. Start eating consciously — because barbaric eating is the basis of barbaric existence.

Eventually, although many might disagree, the use of psychedelics is — in my eyes — incompatible with eating meat, or to be more exact, with eating the industrial meat grown in cattle concentration camps and consumed today in larger doses than at any other time in our civilization’s history. A person who is in close contact with the mushroom (or other psychedelics) will eventually receive, again and again, that same message which calls upon him to forsake this path. He can ignore it once, twice, or even a hundred times — but with many people, the message will eventually be heard. One stops eating meat or limits meat consumption one way or the other; I have seen this happen many times.

Amusingly, even those opposed to the use of psychedelics are aware, in some distorted way, of their influence on our eating habits. This Anti-LSD film from the sixties tells the story of a girl who takes an LSD trip for the first time and goes to a hot dog stand, ready to voraciously shove a hot dog into her mouth, but after she drowns her hot dog with ketchup and mustard she hears a voice. Suddenly she sees the hotdog as a living creature, and the creature begs her not to eat her and take her life. For the makers of the film, this awakening sensitivity is clear evidence for LSD having driven the poor girl crazy.

Carnivorous Cultures and Shroom Cultures

This brings me to the modern meat-addicted consumer society. While the mushrooms ban the eating of meat, carnivorous society bans the eating of mushrooms. Eating meat and eating mushrooms present, so it seems, two mutually exclusive cultural alternatives.

While the psychedelic alternative signifies the potential for a society based on awareness to our body, our ecological surroundings, and our fellow men, the meat society is a society based on:

Destruction of the Body — Eating red meat is, according to many clinical studies, one of the prime factors contributing to cancer, heart problems and many other medical complications.

Ecological Damage – The UN has already declared that the gigantic mass of cattle which is being grown on planet earth, and the great amounts of methane gas emitted by these animals, is one of the chief reasons for global warming.

Economic Damage — Caused by the growing medical expenses needed to take care of millions of meat-stuffed citizens suffering from cancer, heart problems and other medical complications caused by the excessive eating of meat.

Moral Damage — The meat society is based on the mass-killing of life kept in concentration camp conditions. This society, based on sin, cannot help but be a basically violent society — and this is without getting into the more philosophical ideas many spiritual traditions hold regarding the negative effects of meat-eating.

In comparison to the millions who die because of meat eating, there has yet to occur even one case of death which was caused directly by eating mushroom, and while detractors of psychedelics might spread scare stories about people jumping of rooftops, the scientific literature provides evidence that users of psychedelics are not especially prone to psychosis and actually enjoy somewhat better mental health than the general population.

Despite this overwhelming data, our society prohibits psychedelic mushroom eating and allows, or even advocates, the eating of meat. For the carnivorous society which sanctifies the values of war and carnage, the harmonious values of the mushrooms are an intimidating alternative which must be suppressed at any price, because they might raise questions about the entire carnivorous civilization and its values of force and authority.

Eating meat and eating mushrooms are more than just two nutritional options — they are cultural alternatives, different modes of thought: of relating to the body, to nature, to the other. As long as our society chooses to fortify the former by supporting monstrous corporations dedicated to the raising and killing of cattle, and ban the latter with billions of dollars spent on the “war on drugs,” it cannot pretend to be surprised about the bad shape in which our planet and culture find themselves.

* A version of this article was previously published in Reality Sandwich.

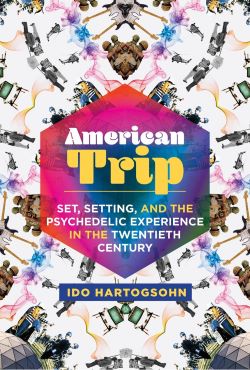

This week the new special edition of the MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies) Bulletin appeared. The theme for the new issue is Psychedelics in Psychology and Psychiatry, and it contains an article I wrote, based on my PhD research, which I’m wrapping up these days.

The article mixes the story of 1960s psychedelic research with some technological theory to offer a new perspective on the role of set and setting, in the story of the psychedelic sixties.

To read the “The American Trip: Set, Setting, and Psychedelics in 20th Century Psychology” by Ido Hartogsohn

To read the entire Spring 2013 MAPS Bulletin.

The article originally appeared in The Daily Psychedelic Video

A few months before Terence McKenna passed away, he gave a last interview to countercultural writer and pundit Erik Davis. The interview, which has since gained mythical status can be listened to on YouTube or downloaded as a podcast from the “Psychedelic Salon” website.

Listening to it recently, my attention was caught by the part in which McKenna discusses the metaphysical meaning of animation and the part where he names some of his favorite cartoons. I then searched YouTube to find some of the cartoons he mentions and enjoyed them quite a bit.

What follows is the transcribed section of the interview in which Terence discusses animation and then the actual psychedelic animation videos which Terence mentions in the interview.

Terence McKenna on Psychedelic Animations – From Erik Davis’s last interview with Terence McKenna

“I encourage everybody to think about animation, and think about it in practical terms. To look at objects, and pose these things to themselves as a model of old problems, because out of that will come a language rich enough to support an actual form of human communication that’s been very elusive and maybe never at hand at all.”

“It’s very interesting when you talk to people or listen to people, how many people who take psychedelics have cartoon-like encounters with beings. And you say: Gee, this is weird, cartoons only go back to 1920 or 1915 or something. How weird that an out there technical phenomena could just grab a whole section of human psychology and camp there with that kind of tenacity. And to me that indicates it has an archetypal claim on that territory”

***

“Well, The great genius of Disney… Disney is my idea of – beyond Edison and Ford or anybody – of what we really mean by an American genius. Because he had mice who wear gloves living inside his head, but he was able to create a mechanical technology to show people these mice. So instead of just being put quietly away by his brother or something like that, he said: “No, no, you don’t understand. Money! This is worth money! If we can show people these glove wearing mice and talking ducks and all this stuff.”

“And then he was a sufficiently American Yankee genius that he saw how to take a flip book and put it on celluloid and do all that. Yeah, I think Disney is a very very far out person. He went to the platonic ideas and came back with baskets full of [???] released them in American towns and cities, and did very well.”

Erik Davis: “Animation is a great place to see the reflection of things that are happening at the culture at large.”

Mckenna: “And certain people take it to incredible Heights. Do you know that animation called “Asparagus”? You should check it out. It’s about 20 – maybe it’s 15-20 years old – but it’s very highly detailed, as realistic as a van Eyck painting, and totally surreal. Also, do you know that one by Sally Cruikshank called “Quasi at the Quackadero”? that’s a DMT extravaganza carnival basically, a cartoon carnival, but a carnival crazy enough to convince you you should go take drugs basically. And Max Fleischer is a genius and all these people.”

-

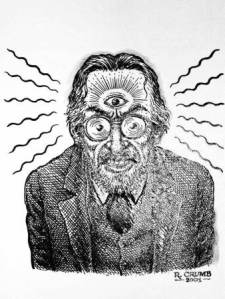

Erik Davis: “Fleischer is great. I think Fleischer is the true origin of underground comics. I think you find the most pregnant images of a certain kind of seedy – like the way that Robert Crumb presents a certain kind of seediness – and sort of failure of the bodies and spaces, and yet that’s infused with a kind of like magical eye. So you really have that both in Fleischer. You really have the mania of the Betty Boom but also a certain kind of quotidian, almost proletarian graininess to these characters.”

McKenna: “Yes, it would be very hard to imagine postmodernity without Crumb’s input. I consider him an absolute psychedelic genius. Very few people have had the influence without the karma that crumb had. He basically did all that stuff, sold the drawings and moved to a chateaux in southern France and called it quits. And got away with it.”

Asparagus – Susan Pitt (1979)

Suzan Pitt’s Asparagus was screened together with David Lynch’s “Eraserhead” for two years on the midnight movie circuit. It has a loose plot, lots of phallic imagery and surreal, psychedelic content.

Quasi at the Quackadero – Sally Cruikshank (1975)

Quasi at the Quackadero is about two ducks and a pet robot who visit a futuristic psychedelic amusement park in which you can view your thoughts, watch yesterday’s dreams, or go visit the past.

Max Fleischer Videos

Max Fleischer was one of the leading pioneers of American animation who worked in animation since the 1910s. He invented the Rotroscope technique which has since been used in films such as Waking Life and Scanner Darkly, as well as a number of other animation techniques. Fleischer’s biggest animation stars were Betty Boop, Bimbo and Popeye the Sailorman. A few of his videos were already featured on the Daily Psychedelic Video: Betty Boop – Ha Ha Ha, Bimbo’s Initiation and the Saint James Infirmary Blues in Betty Boop’s Snow White.

Wikipedia says has this to say about Fleischr’s style of animation:

“Fleischer cartoons were very different from Disney cartoons, in concept and in execution. The Fleischer approach was sophisticated, focused on surrealism, dark humor, adult psychological elements and sexuality. The Fleischer milieu was grittier, more urban, sometimes even sordid, often set in squalid tenement apartments with cracked, crumbling plaster and threadbare furnishings. Even the jazz music on Fleischer’s soundtracks was rawer, saucier, more fitting with the unflinching Fleischer look at America’s multicultural scene.”

Below are three short and psychedelic animations by Fleischer Studios. The first one was banned because of the explicit use of nitrous oxide. In the second one, Betty Boop and her partner Bimbo sell a magic potion by the name of “Jippo”, which can cure every malady and cause fantastic transformations. The third one follows Bimbo through his incredible psychic initiation.

Betty Boom – Ha Ha Ha (Nitrous oxide video – Don’t miss the part starting on 4:00)

Betty Boom M.D.

Bimbo’s Initiation

The article was originally published on the Psychedelic Press website.

“Psychedelics” and “Entheogens” are two names for the same group of psychoactive compounds (usually referred to as “psychedelics”). These two terms delineate two very different perspectives on the proper way to use these psychoactive compounds.

“Psychedelic” is a term which was invented by the British psychiatrist Humphry Osmond in 1957, during a correspondence with Aldous Huxley, as the two were trying to find a new designation for the psychopharmacological group of substances which included compounds such as mescaline, LSD, and the psilocybin (found in magic mushrooms). The new name was supposed to replace terms such as “psychotomimetics” (psychosis-mimicking drugs) or “hallucinogens”, two term which were deemed biased and misleading since they falsely present the type of experiences to be had with psychedelics as pathological or conversely as imaginary and without relation to reality. The etymology of the word “psychedelic” is in the two Greek words: “psyche” (mind) and “delos” (manifesting).

“Entheogenic” is a term whose meaning in Greek is “generating the divine within”. It is used to refer to the same group of substances as “psychedelic”. This term was coined in 1979 by a group of researchers which included prominent figures of psychedelic scholarship such as classicist Carl Ruck, ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes and mycologist R. Gordon Wasson. The neologism was introduced due to a general feeling that the term “psychedelic” has become too strongly identified with the excessive drug culture of the 1960s and damages the unbiased discourse about traditional or religious use of “psychedelics” within a shamanic or spiritual context.

Ever since the invention of the term “entheognic”, the two words have come to designate two different approaches in regards to the proper ways to experiment with the same group of plants and molecules. While the first one relates to mostly free-style experimentation, the other relates to experiences in which religious intention plays a fundamental role.[1]

Psychedelia and entheogenia are complementary in many ways. Both are ways to increase our understanding of the universe and of ourselves; To live more fully, to love and to appreciate. And yet, they are both are fundamentally different paths, defined by fundamentally different attitudes and style. For example, many of those who support entheogenic work (i.e. shamanic or ceremonial use of power plants), discourage the “psychedelic” use of such substances as irresponsible and lacking respect. At the same time, many of those who champion the psychedelic approach regard the entheogenic approach to be too ceremonial, maybe even dogmatic, or just prefer to experiment freely without any ceremonial restraints.

In this essay I would like to examine the roots of these two approaches and assert that despite the major differences, these two approaches can actually complement each other, enrich each other, and give birth to a balanced fertile path for the use of psychedelics.

The psychedelic element

The psychedelic element is chaotic. Psychedelic use nourishes itself on colorful and often surprising interactions between the drug experience and the external world. These are the qualities which make it so interesting. The psychedelic path is epitomized in the figures of Ken Kesey, Stephen Gaskin and Hunter S. Thompson who turned the hallucinating exploration of reality into a form of art. In its root lies a basic call for psychonautic adventure, for a breathless and sometimes even frightening journey into the visionary worlds of consciousness and the symbolic bowels of the world around.

The psychedelic element has a strong relation to liminal states of consciousness, and in this respect those who called the psychedelics “psychotomimetics” or “psychosis-mimicking drugs” were right. This was conceded even by the greatest opponents of the psychotomimetic hypothesis such as Huxley and Leary.[2] However, in contrast to those psychotomimetic scientists who viewed these substances as psychosis mimicking and little else, for Huxley, Osmond, Leary and the other psychedelic researchers, the psychosis-like phenomena which were sometimes part of the psychedelic experience, were of essential meaning, but one to be overcome and transcended. The phenomena also held an important lesson about the nature of madness. As Allan Watts writes in his essay about the psychedelic experience, “The Joyous Cosmology”: “No one is more dangerously insane than one who is sane all the time: he is like a steel bridge without flexibility, and the order of his life is rigid and brittle”. Only the person who understands the meaning of madness, who knows what it means to be insane, can be truly sane. Only the person who understands the depths of insanity can choose sanity in its deepest sense, whereas the sanity of the person who refuses to gaze at insanity is nothing more than a thin and brittle shell under which lies a deep abyss.

The Entheogenic Element

The entheogenic element is centered. In contrast to psychedelic experimentation the entheogenic work is ceremonial and focused around prayer, meditation or healing processes. It takes place in a sheltered environment and often with the guidance or company of other experienced voyagers or healers. Thus, entheogenic work tends to be safer than the sometimes chaotic psychedelic experimentation.[3]

Entheogenia is a boot camp for psychedelia. It Is the school in which one learns the discipline. It gives one tools and techniques for work with psychedelics. It strengthens one, teaches proper ways to work with psychedelics, and deepens one’s knowledge of them. It turns them into allies in the sense meant by Castaneda: it gives a person a safe and sacred environment in which he is able to get to know these substances, to know himself, to become firmer and develop knowledge – a knowledge which enables one to be stronger later when he is in the midst of the psychedelic battle, because he has developed firmness, knowledge and power.

Chaos vs. Order

Psychedelia is characterized by a greater amount of freedom in comparison to entheogenia. Psychedelia allows one to experiment with a wider scope of activities, than the entheogenic ceremony which has a singular and permanent center: to be able to converse with friends, walk around in nature, write, read, draw, watch a movie and perhaps also to put yourself in more extreme surroundings such as colorful parties, the streets of the city, or say a circus.

While entheogenia is a focused, takes place in a controlled environment and is characterized by a well-known and regular order (a shamanic ceremony, or a book of hymns such as those used by many contemporary ayahuasca groups and religions) and seeks to avoid unforeseen distractions, psychedelic use is characterized by its openness to unforeseeable elements, sometimes even it chaoticness. The psychedelic path is one in which the magical state of consciousness unleashed by psychedelics is interfaced with the external (and internal) worlds. Psychedelics act as consciousness fermenting agents, as a kind of magnifying/diminishing/distorting glass which transforms colors, sounds, thoughts, ideas, smells, emotions and what not, and which is used to gain a new perspective on the external and internal world to create an immense variety of experiences.

Psychedelia is the DJ who uses up everyday elements and mixes them into exciting new cosmic combinations. It confronts the unknown and synthesizes novel structures of experience with unforeseeable results: eating mushrooms in a park with your friends and achieving new levels of interpersonal intimacy; Going to the cinema after eating a trip to watch a 3D film and enter a parallel world; Visiting the town where you grew up after many years escorted by a molecule which makes you reevaluate your childhood, your roots and who you are. Then maybe even go to the shopping mall under the influence and get shocked but also understand consumer culture on a whole new level.

The psychedelic state is a state of stimulation. We need stimulation, especially when we are immersed in monotonous everyday existence which leads to apathy. The psychedelic wake-up call frees one for the everyday banality of the domesticated consumer-citizen of late capitalism, thus supplying a basis for deep exploration of inner and outer identity, of world and cosmos. However, the stimulation inherent in the psychedelic experience is also its more dangerous aspect: Excessively rapid and violent jolts might unstitch the frail seams of the psyche. Too intensive psychedelic work with not enough intention, rootedness and processing time can lead to the eruption of a crisis.

Entheogenia functions as a balancing and anchoring element for psychedelia. Both are in a sense a kind of yin and yang: opposing forces or paths which complement each other and give those who stride their course a full way of life in balancing the cosmic elements of chaos and order.

Transcendence vs. Immanence

While entheogenia is focused on creating a a connection with the god-light of oneness, to a transcendental experience,[4] psychedelia is aimed at connecting with the divine within the world, with immanence.

The entheogenic experience is a ceremonial experience which turns its gaze towards infinity/the white light/ensof. It’s highest goal (Even though it is not always achieved or even sought after) is the dissolution of the ego and it’s boundaries and unification with the God/Spirit/the divine through mediation or prayer (Uniomytica). Entheogens act as an accessory to prayer, meditation and healing which allows one to pray or meditate more deeply, powerfully and meaningfully – opening the path to unification with God in a way which is otherwise unavailable to those who are not part of the rare few born with the natural proclivities of mystics, as described by William James in his Varieties of Religious Experience.[5]

The psychedelic experience, in comparison, is more focused in the experience of the world in which we live. It is a re-living, a boosted, enriched re-experience of the things which you already know in the world, and which now gain new meaning and magic. Understanding your relations with a closer person in a new way, understanding art in a new way, relating to nature in a new way, relating to your body in a new way, relating to yourself in a new way. Psychedelia allows one to see every aspect of reality with fresh eyes. It allows one to inject deeper knowledge and imagination into the everyday life in ways which can foster growth.

While the entheogenic experience is often focused in the relation with the unity of things, the psychedelic experience is often related to the experience of the many. Whereas the entheogenic experience is basically a spiritual experience, the psychedelic experience is to a great extent a cultural experience.[6]

The Golden Path

Some people will always prefer psychedelic experiences over entheogenic rituals, while others will feel the opposite way. These differences are to a great extent the result of differences in temperament and style. Psychedelic people are often wilder, more anarchic in nature, less discriminating about using chemicals and non-psychedelic drugs and will demand a more spontaneous, flexible relation to the drug experience. Entheogenic people, in contrast often tend to have a more rooted style of life, with a more structured and regular form of spirituality, and are guided by firm principles about the proper way to use entheogens (which they will never call drugs, but “medicines”). In a way, one could say that psychedelia represents the secular, cultural aspects of the drug experience while entheogenia represents the spiritual aspects.

From my personal perspective it is recommendable for any psychedelic person to explore the entheognic world at some stage in his life (given the opportunity to do entheogenic work with honest experienced people). The entheogenic element is to my mind crucial in preventing the banalization of the psychedelic experience, which might become repetitive and aimless without the clear line supplied by entheogenia. The entheogenic element functions as a balancing force which guards one from the too violent jolts and shakes which sometimes occur due to intensive psychedelic use.

It is hard for me to say whether it is recommendable for every entheogenic person to explore the psychedelic path. While a psychedelic person would normally have no basic principals which prohibit from participating in an entheogenic experience, the religious character of entheogenia sometimes prohibits “recreational use” of psychedelics. The use of power plants for non explicitly religious purposes might seem as sacrilege. Maria Sabina, the legendary shaman who led Gordon Wasson on his first mushroom experience in the Mexican Oaxaca mountains in Mexico in 1955 claimed that after the westerns flocked the area in search of the mushrooms, the mushrooms had lost their power. This can be a valid reason to make a distinction and avoid using a plant with whom we work ritually for recreational purposes. The entheogenic approach to the sacred power plants is imbued with so much delicacy, love and awe that it is worthy of protecting. Truly sacred values, ideas and objects are so rare in this chaotic postmodern world in which we live, that preserving them demands a devout relationship of love and respect, so that they remain this way. For this reason for example many of those who drink Ayahuasca in ceremonial setting would never drink it at home, even though they might do that with mushrooms.[7] However, in my opinion the importance of spiritual work does not categorically negate the validity and importance of the wild psychedelic experience in the style of Kesey, Gaskin and Hunter S. Thompson. That kind of idea, although it might be more politically acceptable, actually ushers in a kind of psychopharmacological Puritanism which many of the proponents of the psychedelic experience such as Leary and McKenna warned us against.[8] And anyway, it is clear than many people have a deep-felt need for both aspects.

***

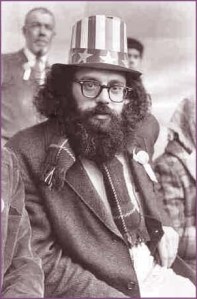

The idea that the psychedelic and entheogenic paths can and should exist side by side is not new. It has been around ever since that historical moment when Allen Ginsberg, the first seer of the psychedelic revolution of the sixties had his first mushroom trip in December 1960. I will close the essay by citing from Timothy Leary’s first (of many) autobiography “High Priest” which describes the original psychedelic vision which Ginsberg had on that day. In a reality where the two schools of psychedelia and entheogenia often seem disconnected or at odds with each other, it is worth going back to the innocence and lucidity of the original vision received by Ginberg:

“And then we started planning the psychedelic revolution. Allen wanted everyone to have the mushrooms. Who has the right to keep them from someone else? And there should be freedom for all sorts of rituals, too. The doctors could have them and there should be Curanderos, and all sorts of good new holy rituals that could be developed and ministers have to be involved. Although the church is naturally and automatically opposed to mushroom visions, still the experience is basically religious and some ministers would see it and start using them. But with all these groups and organizations and new rituals there still had to be room for the single, lone, unattached, non-groupy individual to take the mushrooms and go off and follow this own rituals – brood big cosmic thoughts by the sea or roam through the streets of New York, high and restless, thinking poetry, and writers and poets and artists to work out whatever they were working out.” (Timothy Leary. High Priest. P. 25).

[1] It is important to note that the distinction presented here between these two terms is not as clear cut in the discourse of today’s psychedelic community, and many might use these two terms interchangeably. Also, the word “psychedelic” was used for both meanings in the psychedelic discourse of the sixties, before the invention of the term “entheogenic”. The distinction between “psychedelic” and “entheogenic” presented here is a meant to highlight a basic principle in the discourse of psychonautics, based on the common use of these terms in contemporary psychededelic/entheogenic discourse.

[2] See for example Leary, Metzner & Alpert. The Psychedelic Experience. p. 24.

[3] The number of psychedelic casualties is significantly smaller (up to almost non-existent) in native societies which use these plants traditionally as well as in contemporary ayahuasca religions when compared with recreational psychedelic users.

[4] Even though it has pronounced immanent aspects, in as much as man finds the divine within.

[5] Some mystics can of course achieve entheogenic levels of awareness without entheogenic means. Also, peak experiences which resemble psychedelic peak experiences might happen at certain points in a person’s life such as when falling in love, in the birth of a first child or after 40 hours without sleep. Such experiences however happen very rarely and unexpectedly for most people, and as the late McKenna used to say, psychedelics are the only way we know that allows us to access these states of consciousness quickly, reliably and in a way which can be empirically recreated, with the smallest risk in comparison to other techniques used throughout history.

[6] That is. It can also be cultural, but it will most often also include cultural elements.

[7] Of course respecting and protecting the sacredness of your power plant is a delicate matter even when one partakes solely in entheogenic work.

[8] See for example Paul Krassner’s interview with Leary, published in Leary’s “Politics of Experience”, where Krassner charges Leary that his campaign for the religious use to psychedelia has neglected the rights of all those who simply want “to get high”. Leary defends himself there, proclaiming the right to get high without any particular agenda or ideology to be a basic human right.

The state of psychedelic research: An interview with Rick Doblin

In August 2012, I met Rick Doblin at his home near Boston to interview him for my research about the role of set and setting in the psychedelic debate of the 1960s. We set out on a long walk in the park, as Doblin explained to me the current state of psychedelic research. Lately, I met Doblin at the Psychedemia conference which took place at the University of Pennsylvania in September 2012 and had the chance to discuss the topic with him again. The interview below is based on both those conversations. It was originally published on Reality Sandwich.

***

“You know, it was actually the holocaust that was my main motivation for doing what I do,” told me Rick Doblin, founder of the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), late one night as we are sitting together after a long day of lectures in the psychedelic conference Psychedemia.

“You know, it was actually the holocaust that was my main motivation for doing what I do,” told me Rick Doblin, founder of the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), late one night as we are sitting together after a long day of lectures in the psychedelic conference Psychedemia.

“The Holocaust brought you to psychedelic research? How?”

“It was my recognition that this catastrophic abuse of power and violence was made possible by ignorance, fear, scapegoating and people projecting their shadow onto others. Psychedelic psychotherapy and the mystical sense of unity that psychedelics can generate can be an antidote to all of those things.”

Having a strong metaphysical foundation for your work is probably necessary when that work entails challenging the current status of the law, government agencies, and well entrenched fears; however things are not always that serious with Doblin. Sporting a friendly, seemingly perpetually cheerful smile, and always enthusiastic to discuss the burning issues of research, Doblin, who earned his PhD in public policy from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, looks like the perfect poster boy for psychedelic research. He has been playing a central role in advancing the cause of psychedelic research since 1986, when he founded MAPS, an organization which acts today as the central connecting and facilitating platform for psychedelic research around the world. In the past decade, MAPS has been leading the research on MDMA, treating Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in war veterans. It has also sponsored research on the use of LSD and MDMA for treating patients with end-of-life anxiety in terminal patients, and the use of ibogaine and ayahuasca for the treatment of opiate addictions.

“The way psychedelic researchers are doing this now is that we are focusing on two main fields in making psychedelics available through prescription” says Doblin. “Heffter Research Institute is leading the effort on psilocybin, focusing its research on the use of psilocybin for end of life anxiety, while we at MAPS are focusing on the use of MDMA for the treatment of PTSD”.

More than a life’s work

“Seven to ten years,” is what Doblin says it will take until MDMA is approved by the FDA as a treatment for PTSD, if all goes well. After it is approved for PTSD, doctors will be able to prescribe it off label for other conditions as well which could lead to its recognition as an effective treatment tool for other psychological afflictions.

Seven years might sound like a long time, but the fact that Doblin is even in a position to speculate about when MDMA might be legally available for treatment speaks volumes about the progress psychedelic research has made since he founded MAPS in 1986, a year after MDMA was made a schedule I illegal drug. Doblin’s role in bringing psychedelic research back to the lab might readily be compared with that of the 1960s “Dr. LSD” Timothy Leary, who was responsible in the eyes of some for getting psychedelics illegal in the first place. In a sense it seems as if Doblin, who has dedicated two impressive academic papers to examining Leary’s work in the 1960s and has uncovered some thought provoking flaws in that early research, dedicates his life to fixing the damage done to psychedelic research in the 1960s. While Leary’s work was sometimes criticized by opponents for lacking a rigorous methodolgy, exaggerating benefits and underestimating the safety risks, Doblin has put the emphasis on a cautious, careful approach and rigorous methodology. Most importantly, Doblin seeks to bring the change from within the establishment and not by rejecting or antagonizing it.

“Today, we are more aware that there are complex issues that have to be looked at,” he says “and this also has to be done more cautiously, because we’re coming to a freaked out culture that had a bad trip with psychedelics and we’re trying to talk them through it and work through these things. I feel like there is this growing sense of opportunity for psychedelic research. It’s still fragile but it’s not that fragile, and it’s international, and it has to be done in a really transparent, open way. People are fascinated by this stuff and they should be, it’s all about love, connection, feelings, spirituality.”

You’ve been involved in psychedelic research for 3 decades; bringing psychedelic drug research from research moratorium, into FDA approved Phase 2 trials, and now working to bring them into Phase 3, which will take even more time, money and tackling of bureaucracy. It’s a long and complicated process. Do you see it as your life’s work?

Doblin: “Actually it’s more than a life work. Ten years ago I was very worried that my interest in psychedelics would be perceived by young people as this idealistic naïve idea of the hippies that had been discredited by all the conservative drift and the failure of the sixties. I was worried because it is more than a lifetime’s work, that if it didn’t all get done by my generation it might not ever get done because other generations might not value it; that we were isolated, self-deluded hippies. But what I’ve found is that there are more than enough people in the younger generations who are interested in psychedelics. Most of my staff is in their 20s, just turning 30 or so, and they are really connected to the spirit of what we’re trying to do. That helps me feel that I can try to optimize the timing of initiatives, in terms of when we get our data out, when we have the latest media announcements and so on.”

A lot of people in the psychedelic community have criticized the use of a medical model in the past. It is often noted that most people don’t want to spend a psychedelic experience together with doctors in a medical setting, and that the medical model doesn’t address the full potential of psychedelics. What do you say to that as somebody who stands at the forefront of medical psychedelic research?

Doblin: “That it is totally right. We don’t want a medical priesthood or a religious priesthood, because there are different kinds of benefits. There are physical benefits, marital counseling benefits, spirituality benefits, creativity benefits and recreational, celebratory benefits. My background is psychology, governance and public policy. What I’m trying to do is pick a strategy that will lead to the widespread availability of the legal use of psychedelics. I think that will come through psychedelic prescription medication. In a way we already have legal medical use with ketamine, which is a prescription medicine for anesthesiologists and can be prescribed off-label. The idea of using psychedelics as a medicine is likely to be most in line with what has already happened in the mainstream. The spiritual use of psychedelics is currently limited to participation in small religious groups and plays an important role in changing cultural attitudes, especially the use of ayahuasca, but expanding to personal freedom to use psychedelics for individual spirituality, creativity and personal growth is too close to legalization to lead the way.”

A psychedelic renaissance

For an outside observer, the return of psychedelic studies would probably have seemed highly improbable just 25 years ago. Psychedelic studies had been put on a moratorium at the end of the 1960s and seemed to be a thing of the past that would never be allowed to happen again. However, since 1990, the volume of academic research papers on psychedelics has been rising steadily. In the past decade this growing flow has turned into an impressive corpus of studies about psychedelics coming from labs but also from an increasingly wide variety of academic disciplines, and giving rise to talk of a psychedelic renaissance.

“FDA is willing to do science over politics. That’s the key thing.” says Doblin. “They’re willing to have a rational scientific debate.”

What caused this change of attitude?

Doblin: “The change at the FDA wasn’t actually due to the debate over psychedelics. It happened as a result of something bigger that was going on in the FDA bureaucracy, related to influence from the pharmaceutical industry and Congress to speed up the FDA drug development review process. This led in 1989 to the creation of the Pilot Drug Evaluation Staff, a new group at FDA with the responsibility for reviewing research with psychedelics and marijuana along with medications for pain, headaches and other indications. They wanted to show that they had processes that would expedite drug development and they wanted psychedelic and medical marijuana research to proceed so they could demonstrate their new processes. This led in 1992 to a recommendation by an FDA advisory committee that human studies be resumed and regulated by the FDA the way they regulate any major pharmaceutical company. They FDA got NIDA and the DEA and the drug czar to agree to that by making it seem as if those little non-profit psychedelic people would never get past the FDA drug development system, because according to the pharmaceutical industry it costs more than a billion dollars to get a drug out into the market. But it won’t actually cost MAPS a billion dollars, more like $15-$20 million.”

Why? Where was the flaw in their line of argument?

Doblin: “You have to look at where these numbers come from, which is the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development. The different pharmaceutical companies send financial information about their research efforts to this central place under conditions of confidentiality.”

“First off, pharmaceutical companies are for-profit entities. There is a concept called opportunity cost, which means that while they are investing their money in research for no return, they could theoretically be using it to invest in the stock market or in bonds. Even in this investment climate, they were calculating that they could be earning 12% a year on what they’re spending for research. They may have modified that, but a few years ago that’s what they were using. When you take into account compounding interest, and that these research processes sometimes take 15-20 years, actually half of that billion dollars is this opportunity cost. But we don’t have that because as a non-profit we don’t consider money spent on research as a lost investment opportunity.”

“Then there is another factor, which is that these companies only have a few successes. In fact, they have a lot of failures. So the cost of all of their research effort is amortized over these few successes. So if they’ve spent half a billion dollars but only got 2 success then each one cost 250 million. With psychedelics, we know they work, we just have to prove it, we don’t need to study thousands of different new molecules to come up with a drug that works.”

“They come up with something that’s patentable, so that they can control it, but there is something new about it. So they have to spend a lot of money proving safety. But with MDMA we have the advantage of it also being ecstasy, and governments all over the world have already spent over $300 million dollars on trying to show why it’s bad, with all this research in the public domain. Plus, tens and tens of millions of people have taken it so we know all the side effects that go through emergency rooms. The FDA knows more about MDMA than about any other drug that they have ever approved, and this is true also about LSD, psilocybin and the other classic psychedelics and marijuana.”

“So when you subtract all these costs to pharmaceutical companies that we don’t have to spend, then you start trying to calculate what it will cost you to conduct the research needed to prove safety and efficacy in your specific patient population. One factor is that the larger the treatment effect and the less variability in the results, the less subjects you’ll need. So I can’t tell you how much it’s going to cost but my guess is about $15 million dollars. I think the costs are reasonable, particularly since the research expenditures are spent over 8 years or so, so we don’t have to raise the funds all at once.”

Where do you get your funding from?

Doblin: “Donations from individuals and family foundations have been the only source. No government grants yet, since the government is still in middle of supporting the war on drugs. . No pharmaceutical grants since psychedelics are off-patent and can’t be monopolized and compete with other psychiatric medications that people need to take every day. But overall, controversy has lessened, and the need for new treatments for PTSD and end-of-life anxiety and addiction, has increased. We get support from the baby boomers, some of whom are returning to psychedelics again after all these years of absence while they focused on careers and family. Time is on our side. There are a group of boomers who have been successful financially now getting spiritual again as they get older. These people are helping financially, and also culturally, because these are people with good reputations, people you’d be surprised who had good experiences with psychedelics.”

“I think our chances for private funding are quite reasonable. However, each time we get more data, then the next level is more expensive but also more people are willing to get involved. I have been talking with a foundation in England, and they were considering whether it is a reputational risk or a reputational opportunity for them to support MDMA/PTSD research. Unfortunately, they see it as a reputational risk. This foundation is the largest in England, it has $20 billion dollars in assets and gives away about a billion dollars per year but they are still not ready to get involved, so we have to keep trying with them for another couple of years. We have to get to the end of Phase 2, which will cost about $3 million, and then have Phase 3 which will be about $10-15 million.

When process is completed, what kind of model do you see for psychedelic therapy in the future?

Doblin: “The treatment form depends on the condition that you’re treating. But in general it will be non-directive, client focused, following the emotional threads brought up by patients, both positive corrective experiences as well as working through trauma. I think particularly of using it for end of life therapy, for PTSD. Outside of treating diagnosed psychiatric indications, it can be used for couple’s therapy, for spiritual growth, and even one day for rites of passage at all ages, eventually even to make bar mitzvahs more meaningful, or in your later teens or 20’s to help people decide what they want to do with their lives, and throughout the lifespan. When I turned fifty I felt that I needed a big dose of LSD-assisted psychotherapy just to adjust to getting older.”

Can all of this really fit that within the scope of therapy?

Doblin: “No, because it goes beyond curing clinically diagnosable mental illness. These are existential issues of being alive, not pathologies. That’s one reason why we’re not looking into couples therapy. MDMA could be great for couples therapy, but that’s not a disease. So how do you make it into a medicine for couples therapy? You have to make it into a medicine for a disease and then doctors can prescribe it off label for couples therapy and other conditions. You get it approved for one thing, and then physicians have the freedom to prescribe it for other purposes. But I think it’s initially going to be approved for use only in psychedelic clinics. The therapists will be regulated and the set and setting will be regulated.”

So the set and setting will actually be part of the regulation process? It is actually part of what we look at when we look at the results of research, right?

Doblin: “Yes, and it’s also what the FDA looks at in their regulation. They’ve been regulating the setting in our research studies. They will be talking to us as to what we recommend for the setting. And the setting will initially most likely be similar to the one in which the research was conducted – because that’s all we did in our research: we showed that people got better when they took it in this particular setting. We didn’t show that they took the drug at home, went to the beach, had a great time and now they’re better for their PTSD. We showed that it is effective in a particular setting. So it’s likely that they’ll be requirements for the psychiatrists and therapists who are going to prescribe it. There is going to be a certain kind of training that they’ll have to receive. The training will be in the method that was used to approve the drug. But then it’s also very likely that there will be rules for the setting, the physical location. For example: that there has to be a bathroom that you can get to from your room so that you don’t have to walk through a public space, or that you have to be able to spend the night there, or that there is monitoring and co-therapist teams to make sure someone is not abused or raped by unethical therapists, and that there has to be safety equipment in case of emergencies.

Are there any major opponents for psychedelic research at this point? Is there anybody that is really trying to stop this thing?

Doblin: “I think there are some academics funded by the NIDA who will say that MDMA is too dangerous to be used even once in therapy, because of the supposed toxicity and memory problems. There was a big psychedelic conference in England called ‘Breaking Convention’ in April, 2011 with a panel that was focused on MDMA research. The panel discussion featured a fellow by the name of Andy Parrot who is the leading opponent of MDMA research in the scientific community. As you can see on the video of that debate that’s posted on the MAPS website, he’s got a lonely position that’s really difficult to defend scientifically, and it seems he does that for the publicity and attention. There are not a lot of people left in the scientific community who say that it’s too dangerous to be used therapeutically, but there are still a few, and Andy Parrot is one of them.

Where we’ve got so far with the military, after 15 years of trying to get them interested in MDMA/PTSD research, there was a meeting two years ago with senior Veteran’s Administration (VA) people and senior psychiatrists at a major research university. Unfortunately, the VA people said it was too politically complex for them to get involved at this time but it’s important research and somebody should be doing that. Now we’re trying again to see if things have shifted over time.

The opponents are sometimes parents groups that think that the best way to protect their kids is to tell them scare stories and block research into benefits, because there are supposedly only bad drugs with only risks and no benefits. But this sort of dishonest drug education doesn’t really work. The pharmaceutical companies are not opponents because they just don’t see us as a threat. The DEA is not very thrilled about it, but we’ve outmaneuvered them. The military has got more power than the DEA. The veterans have more power than the DEA, and they want to see this research take place.

A psychedelic driver’s license

The topic of drug legalization has been a locus for hot debate in American society over the years, and one which many psychedelic research advocates seek to separate from the issue of scientific research. When asked about the relation between psychedelic research and psychedelic legalization Doblin says that’s one of the hardest questions.

“It all comes back to the methodology. I think it is better, even from a scientific point of view, for people to disclose their biases. Otherwise you have a conflict of interest. When somebody says ‘what’s your view on this related matter?’ you can say ‘it’s unrelated and I don’t want to talk about it’. However, if you think that prohibition is this vast injustice and is a definitely related area which has also been inhibiting the research, then I believe it’s best to admit that. This is not the least controversial path in the short run. However, our strategy is a long run strategy.”

Still, Doblin argues, we don’t really want all drugs to be available to everybody all the time. Same as with alcohol, regulation will be needed, but a smarter one. Doblin is a proponent of the “drug driver’s license” concept which was also championed by Leary back in the 1960s. It follows the notion that like guns and cars, drugs are tools which can be used or abused. In the same way that a person needs to get a license to drive a car or own a gun to insure his safety and the safety of others, that person will have to go through a certain kind of training to get a license to use a certain drug. More knowledgeable drug users, who were taught to use drugs in a safer more intelligent way, should lead to decreased drug casualties. Also, Doblin argues, since violating the terms of a drug license would lead to its retrieval, users will have more to lose and be more careful not to abuse drugs. “It won’t make the black market disappear, but it will make it smaller, which will make it more difficult to obtain drugs illegally, and it might make people think twice before they do things which will put their license at risk” he says.

Until the psychedelic driver’s license meme becomes dominant, MAPS is doing other work to minimize drug harm. The organization has been involved with different educational activities like the “Psychedelic Crisis” video, which teaches YouTube viewers how to help a person having a bad trip. Another one of these activities has been setting up psychedelic emergency clinics in festivals. “We have been doing this psychedelic emergency service at Boom Festival and at other large festivals where people do a lot of drugs” says Doblin. “We will have therapists and volunteers to help people who need it. The Boom festival, for example, has spent 30,000 euros to provide this psychedelic emergency service. They funded teams that were there 24 hours a day. This work envisions how things might work in a post-prohibition world, because people are going to be using these things recreationally.”

How many emergencies do you have in such a festival, and how do you handle them?

Doblin: “Sometimes over a hundred. The treatment takes place in this large geodesic dome which is separated into different spaces by white sheets. Mostly what we say is: ‘you didn’t intend this to happen but you can see this as an opportunity.’ So it’s more of a therapeutic approach, like short term acute psychotherapy. In a sense, for the volunteers who provide the support, this turns into a kind of training program for therapists. And we don’t have to worry about getting arrested for providing this sort of support because in Portugal drugs are decriminalized which allows having measures to increase the safety of drug use. So at Boom they have people with thin layer chromatography drug testing, and people can bring the stuff that was sold to them and have it tested to say what it really is. And they tell you for free if it’s fake and if it’s pure. That brings you back to the question of legalization. Widespread use by young people in the 1960s, is what has panicked people and then led to the criminalization of research. So now that we got some of the research back, non-medical use is still illegal, and if people get scared of the illegal use they could shut down the research. By focusing on harm reduction, we help prevent that from happening.”

And that depends on the public discourse about drugs and psychedelics. Do you see a sign for change in the way these things are perceived in the general society and culture?

Doblin: “More and more people are hearing the word ‘psychedelic’ being said by doctors wearing suits and ties, so the term ‘psychedelic’ is becoming rehabilitated. The two hardest symbolic obstacles we had to overcome in order to show that the psychedelic renaissance had really arrived were to start LSD research, since LSD is the symbol of the 1960s, and then to start research at Harvard, which is where Leary was. Once those research goals were accomplished, people were like: “Shit! They’re doing this at Harvard!” Recently we had this article in military.com about our initial success in our first MDMA/PTSD study, and it was republished in the Navy Seals website, and reported by the Partnership for a Drug Free America, without saying that this was a terrible thing. Someone just wasn’t paying attention, but that tells you something. Our work with war veterans has really moved us forward. So when you look at the big picture of psychedelics and psychedelic research today, I think things are going pretty well”

The Roots and Future of Psychedelic Visual Media: How Psychedelic Aesthetics Took Over the World.

Originally published on The Daily Psychedelic Video

If one were to judge the state of the psychedelic visual style in 1980, one would probably consider it to be an obsolete fad which receded into the past. Nothing could be further from the truth. Although decades have passed since the psychedelic sixties, psychedelic elements are today deeply integrated into contemporary visual culture from Avatar to videos by Beyonce and Rihanna.

The story of psychedelic visuals did not begin in the 1960s. It is in fact an extremely long tale which stretches from mankind’s prehistorical mystical visions, through the psychedelic revolution of the sixties, to modern consumerist media society and beyond. In order to understand the appeal which the psychedelic visual style holds for our postmodern culture one must get back to the roots of psychedelic aesthetics in the visionary experience.

Huxley’s analysis of psychedelic aesthetics

“Prenatural light and color are common to all visionary experiences” wrote Aldous Huxley in his Heaven and Hell “and along with light and color there comes in every case, a recognition of heightened significance. The self-luminous objects which we see in the mind’s antipodes possess a meaning, and this meaning is, in some sort, as intense as their colour.”[1]

Visionary experiences has many possible characteristics, but the most common of which, according to Huxley, is the experience of light: “Everything seen by those who visit the mind’s antipodes is brilliantly illuminated and seems to shine from within. All colors are intensified to a pitch far beyond anything seen in the normal state, and at the same time the mind’s capacity for recognizing fine distinctions of tone and hue is notably heightened.”[2]

Huxley’s lengthy discussion about the aesthetics of the visionary and psychedelic experience in Heaven & Hell remains one the most perceptive pieces about the roots of psychedelic aesthetics. His rich background as a scholar of aesthetics, a scholar of mysticism and a pioneering practitioner of psychedelic journeys, allows him to examine the issue of the visual characteristics of psychedelia from a large historical and philosophical perspective which is essential if one is to decipher the true meaning of psychedelic aesthetics.

All psychedelic visions are unique, claimed Huxley, yet they all “recognizably belong to the same species”.[3] What they have in common are the preternatural light, the preternatural color and the preternatural significance, as well as more specific architectures, landscapes and patterns which tend to reoccur across psychedelic and visionary experiences. For Huxley this intense color and light was one of the primary and most indelible characteristics of what he called the mind’s antipodes, the unknown territories to which the psychedelic voyager is transported.

Looking at the traditions of various cultures, past and present, Huxley found a common ground between their accounts of the heavens or the fairylands of folklore and the lands of the antipodes. He noted the existence of Other Worlds, mythological landscapes of fantastic beauty in many of the world’s cultural traditions. In the Greco-Roman tradition there were the Garden of Hesperides, the Elysian Plain and the Fair Island of Leuke. The Celts had Avalon, while the Japanese had Horaisan and the Hindu Uttrarakuru. These other worldly paradises, noted Huxley, abound with intensely colored and luminescent objects which bring to mind the psychedelic visionary experience. “Every paradise abounds in gems, or at least in gemlike objects resembling as Weir Mitchell puts it, ‘transparent fruit.’”[4] Wrote Huxley. Ezikel’s version of the Garden of Eden notes the many various stones in the garden, while “The Buddhist paradises are adorned with similar ‘stones of fire’”. The New Jerusalem is constructed in glimmering buildings of shimmering stone. Plato’s world of the ideals is described as a reality where “colors are much purer and much more brilliant than they are down here”.[5]

Huxley introduces many more examples of ancient cultures which establish the import and centrality of glimmering gems and precious stones in various mythologies. The implication he draws from this consistency is that the “otherwise inexplicable passion for gems”[6] must have had its roots in “the psychological Other World of visionary experience”.[7] In other words, “precious stones are precious because they bear a faint resemblance to the glowing marvels seen with the inner eye of the visionary.”[8]

Moreover, Huxley notes, “among people who have no knowledge of precious stones or of glass, heaven is adorned not with minerals but with flowers”. Many more examples follow for the various intensely colored, shiny and often luminescent objects in which man had sought the semblance of the Other Worlds, among them candles, works of jewelry, crowns, silks and velvets, medals, glassware, the vision inducing stained glass windows of churches and even ceramics and porcelain ware. All these, argued Huxley, act to transport human beings into higher realities: “contemplating them, men find themselves (as the phrase goes) transported –carried away toward that Other Earth of the Platonic Dialogue, that magical place where every pebble is a precious stone.” Shiny objects, argued Huxley, remind the unconscious of the mind’s antipodes and so allow us to experience a taste of visionary consciousness.

The human urge to be transported into the numinous realm has found its expression in mythologies and religion, but also in art. Huxley notes a number of artists who used colors in transporting ways such as Caravaggio, Geroges de Latour, and Rembrandt. Indeed, he notes:

“Plato and, during a later flowering of religious art, St. Thomas Aquinas maintained that pure bright colors were of the very essence of artistic beauty”.

Although Huxley argues that this categorical equation of beauty with bright colors leads to absurdity, he also finds this doctrine to be not altogether devoid of truth. “Bright pure colors are the essence, not of beauty in general, but only of a special kind of beauty”: the beauty of works of art which can transport the beholder’s mind in the direction of its antipodes.

Modern taste is often reserved about using intensely bright colors, and prefers the more restrained and undemonstrative palette of minimalism and modernist design. The reason, argued Huxley, is that “we have become too familiar with bright pure pigments to be greatly moved by them”.[9] In the past, pigments and colors were costly and rare. The richly colored velvet and brocades of princely wardrobes, and the painted hangings of medieval and early modern houses were a rarity reserved for a privileged minority, while the majority of the population lived a drab and colorless existence. This all changed with the modern chemical industry and its endless variety of dyes and colors. “In our modern world there is enough bright color to guarantee the production of billions of flags, and comic strips, millions of stop signs and taillights, fire engines and Coca-Cola containers”, and all those objects which in the past might have possessed a transporting numinous quality were reduced by the new industrial consumer market into ordinary banality.

The evolution of psychedelic aesthetics in modern times

The potential of psychedelics to act as powerful catalysts for creativity in general and for visual artists specifically was noted by researchers of psychedelics already in the 1950s. Oscar Janiger who administered psychedelics to artists was immediately flooded with artists enthusiastic to explore their creativity through the use of psychedelics. “Ninety-nine precent expressed the notion that this was an extraordinary, valuable tool for learning about art”[10]. Ron Sandison noted a patient whose style changed completely after a psychedelic experience “and she began to paint in the style she wanted to, which was imaginative”.[11]

Many more anecdotal accounts of the artistic merit of psychedelics appear during these years. However, the great aesthetic shift ushered by psychedelics would only come as a result of their popularization in the mid-1960s. The psychedelic revolution has brought the visionary aesthetic which stood at the center of many works of art and religion back to the foreground of western culture, but now through the prism of the emerging pop culture of the 1960s.

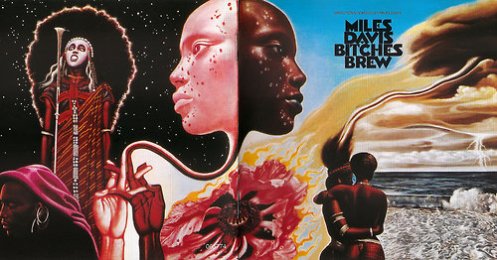

San Francisco psychedelic poster artists such as Rick Griffin, Victor Moscoso, Wes Wilson, Stanely Mouse & Alton Kelley redefined the boundaries of numinous aesthetics by integrating it into commercial psychedelic posters which advertised bands and rock concert. These psychedelic artist, who experimented with colors and forms were inspired to a great extent by the Art Noveau movement of early 20th century and it’s emphasis on organic forms and lines, as well as in the idea of life as art. The aesthetic of these posters would define a new artistic style that would be widely distributed and collected. Meanwhile, psychedelic art flourished outside the poster genre. Visual artists such as Mati Klarwein, Robert Fraser and Milton Glaser designed psychedelic album covers for the likes of Miles Davis, the Beatles and Bob Dylan.

Other forms of psychedelic aesthetics have emerged in various cultural domains. Psychedelic fashion was popularized by rock artists and countercultural figures and even introduced into couture by designers such as Emilio Pucci, Paco Rabanne and Pierre Cardin. Psychedelic light shows by psychedelic light show artists and groups such as Marc Boyle, Mike Leonard and The brotherhood of light became a popular trend in music concerts. (Here one should also note an extremely popular form of psychedelic aesthetics, which is the luminescent culture of Burning Man Festival, whose fascination with glowing colors have turned it over the years into a distinct form of light-worship, a spiritual fest ordered around the heavenly glow Huxley referred to in his work). Psychedelic architectural and inner designs flourished in the communes and were experimented with by a variety of architects and designers as thoroughly documented in the book “Spaced Out”.

What these various genres of psychedelic aesthetics had in common was the use of intensive coloring, extensive use of natural lines, extensive use of op-art as well as of elaborate patterns and designs that sought to transport the viewer into a different state of consciousness. Like the other forms of psychedelic culture, psychedelic aesthetic was a new artistic genre which was rooted in the psychedelic experience and at the same time a cultural artifact which attempted to recreate some of the elements of the psychedelic experiences within the domain of culture.

Yet, by the late sixties psychedelic aesthetics have already left the realms of the counterculture, and started being absorbed by the larger culture, as their commercial potential began being tapped into by various enterprises from Pepsi and McDonalds to Campbell and General Electric so that by the mid-1970s, the psychedelic visual style had been largely absorbed into the mainstream consumer culture which the hippies sought to change.

The evolution and reemergence of psychedelic video

Psychedelic art, fashion, design and architecture were all contributed greatly to the creation of a psychedelic culture expressed in various artistic forms. Yet when it comes to reproducing the psychedelic experience, it seems that film and video had an altogether different potential. Psychedelic visions are after all not not static, buy dynamic and related to sound. An effective use of moving pictures and a soundtrack can powerfully recreate elements of the psychedelic experience. This would appear to be part of the reason, why psychedelic film and video would achieve an even greater popularity than did the more static reproductions of the psychedelic experience such as art, fashion, design and architecture.

Already Huxley noted in his Heaven and Hell that the equivalent of the magic-lantern show of earlier times is the colored movie. “In the huge, expensive ‘spectacular’, the soul of the masque goes marching along” wrote Huxley. He was fascinated by various films with visionary properties, such as Disney’s The Living Desert and claimed that film has the power to create a “vision inducing phantasy”. Psychedelic elements have actually emerged on film already as early as the 1920s as could be seen in this short silent animation film from 1926 as well on Disney’s 1940s films Fantasia and Dumbo the Flying Elephant, which both contained elaborate psychedelic sequences, and whose chief visualist is reputed to have participated in Kurt Beringer’s mescaline experiments in 1920s Berlin.

The 1960s psychedelic genre of film distinguished itself through such films as “Psych-Out” (1968), “The Trip”, (1967), “Easy Rider” (1969) and of course the Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine” (1968) and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey which was frequented in cinema by numerous tripping hippies who immensely enjoyed the closing hyper-psychedelic 30 minutes sequence.

And while the attraction and novelty of the psychedelic style seemed to diminish in the beginning of the 1970s, the attempts to recreate the psychedelic visual aesthetic on film kept evolving. Experimental movie makers such as Vince Collins and Toshio Matsumoto explored psychedelic aesthetics throughout the 1970s, while new motion pictures introduced movie-goers to more elaborate and sophisticated cinematic renditions of the psychedelic experience, created about with the help of new production techniques and technologies in films such as Ken Russel’s 1980’s Altered States and Terry Gilliam’s 1998 version of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

But while these might seem as solitary examples, a far deeper cultural momentum was at work, advancing the integration of psychedelic aesthetic into popular culture. As I showed above, Huxley already noted the visionary aspect of commercial designs such as colorful printed advertisements or neon lights. As technology and media evolved side by side with late capitalism, psychedelic aesthetic and consumer society would find a common field of resonance. Electronic media, which media theorist Marshall McLuhan described as humanity’s nervous system, and which Erik Davis called a technology of the self, would become a new and most effective form of consciousness altering medium. The visual properties of psychedelics, which expressed themselves not only through color but also through a new and more dynamic approach to video editing, would become integrated into the popular culture, while better, bigger screens and higher resolutions created a distinctly psychedelic hyper-real quality in many of the new clips and videos.

And so, while it might have earlier seemed that psychedelic aesthetic became a thing of the past, a quick examination of today’s popular culture would teach us something radically different. Psychedelic visual style is to be found in the music clips of the many of today’s leading music artists, and not only alternative groups such as MGMT, Chemical Brothers or Birdy Nam Nam but also in the music clips of many of today’s leading pop artists from Beyonce to Lady Gaga, Rihanna, Kesha and Nicki Minaj. Psychedelic visionary aesthetic also became an integral part of today’s commercial world from Takashi Murakami’s impeccable Louis Vitton’s commercials to commercials by Sony, Hyundai and Yoplait. Psychedelic videos are being created today, by web users, as well as by commercial firms and popular artists at a higher rate than ever before.

This does not mean that all these videos are psychedelic in the same way. One could distinguish between more superficial use of psychedelic motives characterized mostly by psychedelic coloring, design and editing, which can be found in more mainstream oriented productions, and more distinctly and explicitly psychedelic videos which include more hardcore psychedelic motives such as multi-perspectivism, multi-dimensionality, figure transformation, mandalas and fractalic imagery. In this way one could distinguish between soft-psychedelia and hard-psychedelia.

“the self-luminous objects which we see in the mind’s antipodes possess a meaning, and this meaning is, in some sort, as intense as their color” wrote Huxley. “Significance is here identical with being”. In this, Huxley wished to point out that in contrast to surrealism, for instance, the psychedelic aesthetic is not symbolic of anything else. It is the thing itself. Its beauty needs no explanation, for it is self-evident in its color, richness and harmony. The meaning of the psychedelic visuals is “precisely in this, that they are intensely themselves”.

And this is perhaps what makes psychedelic aesthetics so appealing to today’s popular culture. The psychedelic aesthetic style, which is rooted in the visionary Other Worlds described by the mystics of humanity, is so successful precisely because it is distinguished first and foremost by its “suchness”; because it does not symbolize anything concrete, and can hence be seen as arguably indifferent to content and used for a wide variety of purposes. At the same time the powerful responses it evokes, a result of mankind’s age old fascination with the colors and light which characterized the psychedelic visions of the Other Worlds, turn it into such a powerful mind-altering tool for media.

The future of psychedelic media

One might ask whether the use visionary elements in consumer culture still holds and delievers the deeper psychedelic values, or whether psychedelic visual style has become abused by other purposes. One thing should be clear, however: psychedelic aesthetics in media are here to stay. They are integrated into the cultural production system, and new technologies such as 3D screens and video glasses are about to make them ever more effective and powerful.

The advent of 3D screens, which are making their way into the consumer electronics market these days are one factor which is bound to make psychedelia an even more prominent force in our visual culture. The psychedelic experience has always been about perceiving new and unimagined dimensions, and the addition of a new dimension to media, has an inherently psychedelic quality to it. As a genre which is based on bending our perception and creating rich media environments to inspire awe, psychedelic visuals can benefit greatly from the new possibilities unleashed by the new dimensions. Indeed, Avatar, the most successful 3D film up to date, is distinguished by its extensive use of psychedelic aesthetics. Meanwhile Independent psychedelic video makers have already started to integrate the 3rd dimension into their works with mesmerizing results. The first examples of 3D psychedelic videos are so much more psychedelic and transporting than 2D psychedelic videos that this suggest that psychedelic videos will profit from the integration of the 3rd dimension into media more than any other genre of video.